by Praveena Shivram

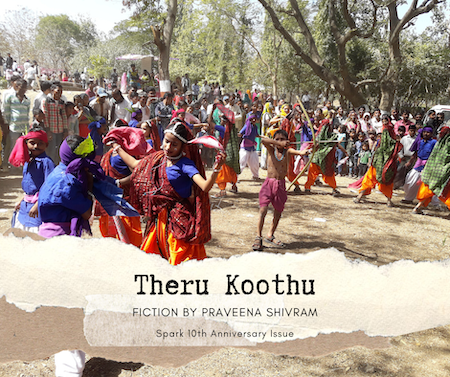

When differing dreams coexist in the same space, passion oscillates between the comforting embrace of the familiar and the beckoning arms of the unfamiliar, often coming to a rest when one least expects it. Praveena writes the story of Malarvizhi, a teenager in Chennai.

The beat of the drum yanked her to her feet. She followed it, through the narrow outline around the settlement by the Adyar River, unmindful of the puddles of water the rain had created the previous night, dodging the women in their nighties with a dupatta over their shoulders carrying plastic pots of water, ignoring the angry cries of children playing cricket as her feet graced the make-shift stumps, and ignoring the lady by the roadside making idlis for breakfast that morning – her mother – calling out to her ‘Eh, Malarvizhi, where do you think you are going? Nillu di, Malarvizhi!’ She walked ahead, the sound of the drum becoming louder and louder, coursing through her veins like a drug, till her breathing fell in step and she was there.

He was MGR today – the sleeves of his t-shirt knotted around his thin arms tightly, a light shade of pink lipstick beneath the pencil moustache, powder patches on his face now becoming stark under the strong summer sun – surrounded by a group of five other actors dressed in black lungis and red shirts.

‘Naa aanai-ittal, adhu nadanthu vital, indha yezhagal vedhanai padamaataar’

If what I decreed could happen, then the poor wouldn’t suffer anymore.

The famous MGR song blared from the speakers, making the crowd break into automatic applause as “MGR” pranced around in his unique style, delighting spectators with his impromptu handshakes and hugs. Malarvizhi was stuck at the back of the crowd, standing atop a parked scooter to watch.

This was the third day of the street performance and it was happening today at the open ground right next to their slum. The first day they performed in the local school and the second day at a private function for the local thug. At both venues, Malarvizhi had managed to find a spot – the back wall for the school and a high tree branch for the thug. Malarvizhi watched, her mind quickly tuning off from the political undertones and jokes the performance usually veered towards, but alert to the performers’ every nuance and gesture. There was only one woman in that group – short, dark and stocky – so Malarvizhi knew she had a chance. She was tall and dark, with a full figure that her mother tried desperately to cover by stitching her loose tops. It did not matter to Malarvizhi, because she knew, whenever she wanted, all she had to do was suck in her breath and walk against the wind. At fifteen, Malarvizhi already knew that her only companion, and a powerful one at that, was her body.

‘Hello! What are you doing on my bike?’

Malarvizhi looked down into the face of a portly man with his moustache quivering in indignation. She hopped off the bike, making sure she gently grazed him and said ‘Sorry, anna, I was watching the theru koothu*’ and flashed him a smile, remembering to suck in her breath. The man immediately shifted his gaze to her chest and smiled back.

‘No problem, ma. What’s your name?’ he said, his hands reaching out to touch, maybe her head, but Malarvizhi was already on her way, her words floating behind her like happy balloons, ‘You will soon see it on TV, anna!’

She raced back to her house and tuned into Jaya TV to watch her 10 a.m. show – do-it-yourself beauty tips. She sat there with her pocketbook and pencil, next to the open airbag that had three of her salwar sets thrown in and two skirts, taking down notes, and calculating the cost of the products during the ad breaks. She would need to snitch some turmeric from her mother’s frugal kitchen, and maybe some lemon and milk too. But honey and saffron were going to be tricky. Maybe besan powder from the Gujarati family in the neighbourhood…

Malarvizhi’s phone buzzed. It was Arul calling her. Again. She cut the call for the tenth time that day. She had put her phone on silent because his first call, that had come in at 4 a.m, had woken up her mother, who cursed into the night about bringing up a prostitute instead of a daughter and threw whatever her hands could reach for in the dark – a steel cup, a Tamil magazine, a candle – in Malarvizhi’s direction. Malarvizhi was thankful that she was some distance away, otherwise her mother’s calloused hands would have found their mark instead. In that one-room house, her mother sleeping in one corner near the space they called the kitchen, and Malarvizhi in the other corner near the asbestos door, their boundaries might have been fickle but the void of reserve was not. Malarvizhi had quickly put her phone on silent, pulled the thin blanket over her head forcefully and gone back to sleep.

Arul ran a local dance school in the slum, teaching young boys and girls freestyle dance – a mix of hip-hop, breakdance, popping and folk dance – pegging his dreams on entering a reality show and skyrocketing to fame and success. They would practice on the terrace of the government primary school, and already, within three months, Arul had students on a waitlist. The reality show carrot was irresistible and for Malarvizhi, like many others, it had already assumed mythic proportions.

Ever since she could remember, she had known she was meant to be on stage. She was a natural performer, delighting her mother and the neighbourhood women when she was younger with her impromptu dance shows and acting prowess. She could transform from Jyothika’s “Ra ra” to Simran’s seamless dance moves, and was always invited to dance in first birthday parties and engagement functions. Malarvizhi knew just how heady it was to have the eyes of the world on her that despite its rapidly expanding universe could be contained in a screen size. She was meant to shine out from amidst that blue, irresistible glow.

She had joined Arul’s group a month ago, after being on the waitlist for six weeks. Arul, a B.Com graduate without a job had decided to put his skills as a dancer to use, and had a rigorous round of auditions to select his students. Those selected – only fifteen at any given time – had to pay upfront for the month. Malarvizhi remembered literally jumping for joy when she had been selected. She had then begged her mother to give her the five-hundred rupees for the month, and when she had refused, had waited for her mother to get drunk – her Saturday night routine at home. She would be watching an old movie on TV with her quarter bottle of rum, telling Malarvizhi stories of her youth, of the time she used to work on a cinema set as a cleaner, where she met the man who would become Malarvizhi’s father, a lightman, a bald lightman with burnt hands from the heat of the lights, who would leave her when she got pregnant but send her money, nevertheless, once every few months. Malarvizhi had waited for her mother to get drunk, pass out, and then slipped her hands into her mother’s blouse, pulled out the frayed cloth purse and taken one crushed five-hundred-rupee note, put the purse back in, and kissed her forehead. ‘Thank you, my sweet Amma. When I become famous, you will see me on this TV and I will bring you a garland of five-hundred rupees. Promise!’

For ten days, Malarvizhi had spent her mornings at home anticipating her classes in the evening, the grinder that they had got free the previous election whirring in the background – she had quit school a year ago when her mother had felt ‘padichadhu porum, now learn something useful’ – and spent her evenings sneaking into the school for her dance sessions. For ten days, Malarvizhi felt that with every click of Arul’s fingers keeping beat to the song during the two hours of practice, Malarvizhi was hearing the beats of her own imagined future clearly, like someone had plugged in a pair of earphones and cut out the noise. For ten days Malarvizhi felt the triumph of someone jostling for space inside the bus during peak-hour and making it. She was the star of her own show and for ten glorious days, no one had switched the channel.

The day the theru koothu came to her locality, when Malarvizhi came back home from practice, she found her mother in the middle of the living room, a quarter bottle of rum next to her, half-finished. It was a Wednesday.

‘Va di, naan pethe penne. Did I really give birth to you?’ Malarvizhi stood where she was, willing herself to stay still and not become consumed in another kind of movement, the kind her mother seemed to be swirling in, a whirlpool contained in one spot.

‘What did I not do for you, tell me. Everyone said “don’t have this baby by yourself”, but I said you were saami’s varam, god’s gift, and I kept you, I raised you, alone, without a man. And I fought hard, you listen, I fought hard to protect you. I even gave you an education. And this is how you reward me? By dancing in a troupe? Shaking your hips and breasts? You think you own your body?’

As she watched her mother ride another wave of tears, the alcohol impossibly magnifying the rigours of daily life and overwhelming the two women inside a small house nursing very different dreams, Malarvizhi knew, as she stood still like a placid lake, that she was going to have to leave her mother behind. It came slowly, this drip-dropping realisation leaking into her mind that her mother had shrunk and she had grown, while she watched her mother vomit on the floor, then cleaned up the mess, gave her mother some water and crocin, and put a pillow under her head.

‘Thangame… I had them too, you know? Dreams, of becoming something, of escaping this, this life. It comes to nothing. But a child… you, Malar, are precious. Sariya?’

Malarvizhi lay down next to her mother, hugged her tight, and fell asleep. She dreamt that night that she was Jayalalitha, her cheeks pink with rouge and her eyes outlined with thick kajal, singing a duet with MGR, as he danced around her and squeezed her arms. When she woke up, she could smell Jayalalitha’s perfume and MGR’s aftershave, an intermingling of a future that Malarvizhi knew was hers. If she took it.

That was two days ago. Forty-eight hours during which Malarvizhi felt her mother’s relief like the tarpaulin sheet sheltering them from the rain; forty-eight hours in which Malarvizhi knew the shelter was not for her, because MGR had shown her something else. Malarvizhi smiled, the tired smile of a grown-up carrying the temporality of time, as she switched off the TV, zipped up the airbag, raided her mother’s kitchen for whatever she could find, and left, under the Tamil magazine next to her mother’s pillow and rolled-up bedding, a crisp five-hundred-rupee note. It was the advance she had received from the theru koothu team the previous evening with the promise of joining them later the next morning, while her mother was wrapping up breakfast. She debated leaving a note for her mother, but that felt too morbid for Malarvizhi – she wasn’t committing suicide.

Without a backward glance, she stepped into the sun, closed her eyes and took a deep breath and put one leg forward, when someone from behind her screamed, ‘Akka! Stop!’ and Malarvizhi froze, her eyes flying open. She had missed a manja thread by a whisker, as a fleet of young feet ran past her, catching the thread, one of them saying, ‘Sorry, sorry, akka!’ before they disappeared round the corner. The red kite, above Malarvizhi’s head, floated into the blue sky, undeterred and untouched, and Malarvizhi sucked in her breath and walked against the wind.

Praveena Shivram is a writer based in Chennai, India, and currently the Editor of Arts Illustrated. She has written for several national publications, and her fiction has appeared in the Open Road Review, Jaggery Lit, Desi Writers’ Lounge, The Indian Quarterly, Himal Southasian, Chaicopy, and Helter Skelter’s anthology of New Writing: Dissent. Read her work at www.praveenashivram.com

* Theru Koothu literally translates to ‘street drama’. Colloquially it is used to denote a street performance, but traditionally is also one of Tamil Nadu’s folk art forms.