by Ranjani Krishnakumar

“Arakkanga-da neengallaam. Oru naal, arrakkan kayilirundhu vidupaduvaal Kannagi!” screams one of the lead characters of Karthik Subbaraj’s upcoming film Iraivi, “A tale of a few woMEN” at the far end of its trailer.

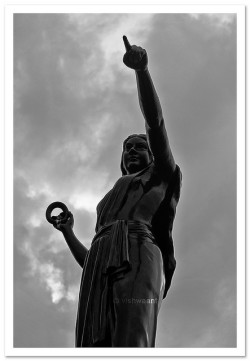

Kannagi makes for an incredible muse. She has fascinated several Tamil film writers, who pulled various colourful threads of meaning from her into a coherent (or not) identity of an ideal Tamil woman. She stands still behind the walls a small temple. She also stands tall — on again, off again — by the Marina beach in Chennai, angrily holding up her anklet, an unusual symbol for justice. She is a goddess. And as Egnor argues, she is one with power or sakti — enough to burn down a city, as she almost did — that she carefully gained with her chastity, “patience (porumai) and endurance (thaangum sakti)”.

She is a Tamil woman, born of Tamil sangam literature — Ilango Adigal’s epic Silappadikaram. She is enduring and forgiving — awaits her husband’s return from his adulterous relationship with Madhavi. She is devoted to her husband — would give up her last financial reserve (her anklet) to rehabilitate her husband. She is chaste. She is powerful. She demands justice and makes systemic changes to get it (well, in a manner of speaking!)

She fit squarely into the Dravidian movement’s anti-establishment agenda, and the ‘revival’ of Tamil pride. Her story — along with that of Vasuki, the devoted and valorised wife of Tamil poet Thiruvalluvar — was upheld as proof that the Tamil land, even in ancient times, was evolved and cultured, with its citizens valorous, virtuous and righteous, and its kings just.

Kannagi’s story — Silappadikaaram — came to print in the 1890s, and to stage drama soon after. When drama moved to the big screen in the early days of Tamil cinema in the 1930s, Kannagi found her new home, a place where she continues to live in various forms.

In its original form, Kannagi’s story — including her husband Kovalan, his lover Madhavi, the erring king Nedunchezhiyan, and his queen Kopperundevi whose anklet was stolen — has been told on screen four times: in 1933, 1934, 1942 and 1964.

In adaptations and retellings, her story continues to be told to this day! In the 1950s, in the heyday of the Dravidian movement, literal and metaphoric Kannagis and Madhavis were abundant in Tamil films — the womaniser’s wife and mistress of Rathakkanneer, the courtesan of Parasakthi, the mother and the whore of Manohara and so on. The comparison of pantsuit-wearing, tennis-playing rich women, with the chaste, poor, enduring Kannagis who devoted their life to their husbands, was a common moral science lesson in films of the times.

As the clouds of the Dravidian movement began passing Tamil cinema, leaving behind a slight and discomfiting petrichor, K Balachander (KB) retold Kannagi’s story in different, confusing ways. He re-moulded the man-leaves-wife-for-another-woman story and misshaped the Kannagi-Madhavi paradigm. One could read Iru Kodugal as having two Kannagis, or Kalki as having two Madhavis. While KB’s Madhavis were often intelligent, out-spoken and had a loud open-mouthed laughter, his Kannagis were portrayed as lacking in something that Kovalans wanted — in some cases, the veryintelligence (which they prized in Madhavis), but in more than one instance, a child.

KB was the flag bearer for Madhavis in several ways — he gave them more agency, perhaps even more acceptance and character than the Karunanidhi era was kind enough to afford them. However, he often reconciled his Madhavis’ errant behaviour by writing for them a life of exile, much like the original epic’s Madhavi (Sindhu Bhairavi), child donation (Iru Kodugal, Sindhu Bhairavi and Kalki) or sacrifice (Puthu Puthu Arthangal). In the best case, the shoulder of a trusted friend, who gets accepted as her lover without a choice, as in the case of Kalki. In a manner, KB replaced the stigma of being a stealing courtesan from Madhavi, and endowed her with certain legitimacy, often earned by voluntarily ending the relationship with Kovalan (even against Kannagi’s own wishes to be in a three-way marriage).

On the other hand, Balu Mahendra’s Kannagi of Marubadiyum — ever so politely and calmly — goes on to forge her own path, one of motherhood and independence, while his Madhavi goes nuts. A lyrical summary of the co-dependence of Kannagi’s and Madhavi’s identities is in a song in the movie that Kannagi’s friend and confidante sings, “Kovalan paadhai thannil, Madhavi vandhadhundu. Maadhavi illai-endraal Kannagi yedhu indru” (In Kovalan’s path came Madhavi; without Madhavi, there isn’t Kannagi). But Balu Mahendra’s Kannagi refuses to take her Kovalan back, when he returns rejected. She applies the rules of chastity that apply to her — appears she applies it to herself — to Kovalan too.

Bharatiraja’s murderous-for-the-right-reasons Madhavi of Mudhal Mariyadhai is, in fact, the Kannagi who dies with her lover!

As Tamil cinema moved to incorporate modern, city-based lives and the computer generation, the Silappadikaram storyline faded into distant memory, but Kannagi stays on and lets herself be interpreted in new and improved ways. Madhavis left the mise en scene as the mirror that tells Kannagi that she is the most chaste of them all. But Kannagis firmly remained, and served their purpose in embodying an ideal Tamil woman. One of the most common ways in which this manifested was in the ‘taming the urban shrew’ trope. Women, the non-Kannagis were carefully sculpted into Kannagis. From Pattikkaada Pattanama to Priyasakhi, a woman who dared not to be devoted to her husband finds her equilibrium only when she returns to her husband’s home, often with a child to raise. The non-Kannagis who don’t get tamed, end up alone or die, from Aval Appadithaan to Ko.

In the 1990s, lyricist Vairamuthu’s Kannagi stood for something fresh. He placed Sita, who was usually painted with the same brush of chastity, suffering and sacrifice as Kannagi, on the passive end of a spectrum of feminist “revolution”, with Kannagi occupying the more active end — “Puratchigal edhum seyyaamal, Pennukku nanmai vilaiyadhu, Kannagi silaithaan ingundu, Seethaikku thaniyaai silayedhu! (There is no good for women without a revolution; there is no statue for Sita, only one for Kannagi).

Fifteen years since, Dhanush wrote his own Kannagi story. As he mourns his torturous love in a drunken ballad “Kadhal En Kadhal” in the film Mayakkam Enna – he describes his ‘figure’[1] Kannagi as a deer eyed, sweet songed, parrot, a sadistic figure, who he wants to beat into disappearance. She, of course, goes on to become his devoted, abuse-enduring, well-wishing, eventually forgiving wife! While lyricist Dhanush’s favourite literary tool appears to be mockery/sarcasm, director Selvaraghavan’s sense of irony completes the story.

Somewhere in between, Kannagi also kindled the romantic dreams of an underground hip-hop artist (who has since come above ground). In a dreamy melody, Hip Hop Thamizha singles out the “senthamizh (chaste Tamil) girl” who catches his fancy and describes the ways in which he likes her — she is a sari-wearing, Tamil-speaking girl who is demure, modest, chaste and beautiful with a small waist and dark tresses, and can turn into a red-eyed Kannagi (only when provoked for righteous reasons, of course!)

As I walk alongside Kannagi, an invisible, hind-sighted companion to her journey as the Tamil filmmaker’s favourite female muse, I stare at the mirror that’s held up in front of me and dream for Kannagi the same thing that Karthik Subbaraj does: “Oru naal, arrakkan kayilirundhu vidupaduvaal Kannagi!” (One day, Kannagi will free herself from the demons!)

[1] In Tamil, the English word ‘figure’ is used to describe a woman attracting a man’s romantic interest. It is often used derogatorily/disrespectfully; almost never used to describe a married woman.

Pic by https://www.flickr.com/photos/vishwaant/