by Sarba Roy

The last time I visited her, she could barely manage to sit upright on the wooden bed. Her back, bent to the will of severe arthritis, gave her posture the appearance of an acute angle, diminishing in degrees with each passing day. The eroding spine was held in one piece and saved from snapping into two by a brace tightened around her upper body. I could tell that it affected her breathing. She’d fiddle with its edges from over her supersized blouse when nobody was looking. But everybody was always looking: obliquely and rather helplessly because there was no other way. None of us were ignorant of her discomfort, we were slaves to its necessity.

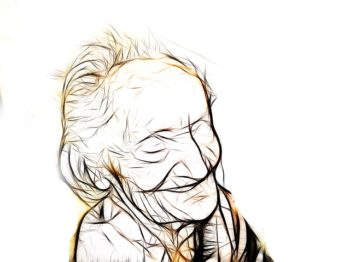

I edged closer to study the lineaments of her face before engaging her in a conversation. Her wrinkles ran like contours along the sagging skin, her eyes a shade of golden yellow, splattered with streaks of red on the edges, her lips curved down with the burden of age. Her dark complexion emanated a radiant glow. No wonder my fair and handsome grandfather had fallen in love with her.

Two successive brain strokes had rendered her memory erratic. At times she’d remember only names, at times only faces. And at times, neither. I still remember the look on my mother’s face when it took dida a little more than five seconds to recognize her own daughter. But my mother gulped that pain down because in comparison to dida’s, it would always be lesser. So, conforming to the practised method, I leaned into my grandmother with a smile that belied my discomfort.

‘How are you, dida? Do you recognize me?’ I chuckled in a casual tone.

She looked at me rather sternly, as if questioning my audacity and then transformed it into a smile, the transition making itself visible in those moist, bulging eyes. She cupped my chin with her trembling fingers and moved them to her lips. And while kissing their tips, she laughed through her platter of half-absent teeth: ‘You’re my beloved grandson!’

Her words seemed to have infused a breath of fresh air into the room. Everyone suddenly emerged from their exiles of melancholy and started laughing and clapping. That our spirits could be lifted by something so simple was a feeling hitherto unknown to me. This fragile creature with protruding eyes, an incomplete set of teeth, a curved body, incoherent words and incomplete memories reminded me of a child. And yet here she was, at her wilting eighties but with strength enough to challenge the flow of time itself.

Amidst all the ecstasy that resultantly ensued, I sat there recalling the stories that my mother used to tell us about her. My grandmother got married at the age of sixteen. And details of her daily chores could convince you of the existence of superheroes. She used to wake up at the stroke of dawn and by the time the birds started chirping, she’d already have completed her ablutions and cleaned and wiped the entire house. She was the first bride in the family and feeding the brood of thirty-odd people was entirely on her shoulders. Having fed the household with their morning meal, she’d take to the pond for washing clothes, utensils and herself. After appeasing the Gods with fresh flowers and other offerings, she’d restart the mammoth task of preparing lunch for everyone. In the meantime, her children would be back from school and had to be tended to. Their bickering and arrogance had to be handled with care while making sure that the food wasn’t spoiled. My grandfather was the sole breadwinner for the family. So, it rested upon dida to ensure that the resources were properly rationed. She’d spend her afternoons knitting clothes for her children. She’d pick up a skirt that wasn’t torn and a top that wasn’t soiled and knit them together into something new. Her days used to end with an equally massive preparation of dinner, this time assisted by other women of the house. And the cycle kept repeating itself day after day, month after month, year after year, interspersed with five pregnancies that made matters worse.

The only person in that room not rejoicing in the euphoria was my grandfather. He was staring at his wife with almost the same expression as I was at my dida. His demeanour, though, was mingled with a visible shade of remorse and regret. I still remember that night when my mother sat frozen on the sofa, the mobile phone pressed so tightly to her ear that the surrounding skin had reddened. My grandfather was crying over the phone, confessing to my mother how sorry he was for not having helped his wife at a time when she needed him the most. For having silently witnessed the degradation of her body bit by bit every single day. For having spent beyond his means for the upbringing of his boys, who, through their actions, make their ignorance of this fact abundantly clear. I’m not in a position to judge the complexities of love. But I do believe that a man with regrets is his own reckoning. And to let him be is the natural course of justice.

The clamour was finally let up by a fetid smell whose origin could not be sniffed out for a while. Upon discovery, my mother asked us all calmly to vacate the room, doing her best to not make a scene out of it. Dida had soiled herself and was looking away. We made our way out, doing the best we could to act aloof of that information. Dida had almost no control over her nervous system or bowel movements anymore. It was a common occurrence. Sometimes she wouldn’t even realise the things she had done absentmindedly. What she did realise though, was the shame that she associated with her actions, irrespective of our repeated assurances.

I made my way to the muddy courtyard sprawled around the thatched kitchen that lay separated from the main house. The traditional chulha wasn’t used anymore. I peeked inside to find it deserted, entangled in cobwebs and home to an array of insects. Not many years ago, it used to be the lifeline of the house, throbbing with commotion and humdrum like the heart of a giant beast. The room attached to it was a storehouse for vegetables and was occupied by a bed on which dida would stretch her legs or take a quick nap. I have my fondest memories of her in that room. In her breaks between successive courses of a meal, she’d regale us with stories of her childhood. Sometimes, she’d express her disappointment in her daughters-in-law who never bothered to come down and provide her a helping hand. These were things she shared in confidence solely with me and my brother. In retrospect, though, it was clear that there could have been other recipients if only anybody had bothered to listen.

My grandmother’s place is situated near Arambagh, a three-hour ride from Kolkata. Even after countless attempts at persuasion, neither dida nor my grandfather would agree to come and stay with us.

‘Who’ll take care of the cows?’

‘Your dida vomits inside vehicles.’

‘Wouldn’t it look bad if we suddenly left? What would my son think?’

‘You’re my daughter. How can I bother my son-in-law this way?’

The reasons were endless. Sometimes they’d enrage us, sometimes we’d understand. Sometimes we’d snap back at him when after a bad day, he’d urge us to look for old age homes. Neither his younger son nor his wife and their children paid him the respect that he once yielded as a teacher of the village school.

It was almost evening and hence time for us to leave. Constrained by the demands of both my parents’ workplaces, we couldn’t afford to stay the night. We took our time bidding dida goodbye. Tears flowed in abundance – even dida managed to shed a few – and tongues clicked in unison against the frame of a setting sun. The garden surrounding the house, which once boasted of every imaginable vegetable and fruit, lovingly tended by dida, now lay scanty and withered, sold one tree at a time to the highest bidders. Age had indeed descended upon every living being in that place. And the youth that followed wasn’t interested enough to hold onto its past glory.

One last glance at that place from the car window brought to my mind an obscure image of a withering symbiosis. Man, nature, men and their natures – all at odds with each other around a bent woman silently bearing witness to the erosion of her carefully built relationships.