by Chandramohan Nair

The auto rickshaw sputtered through the narrow and congested Kochi roads for ten uncomfortable minutes before depositing me in front of an unpretentious concrete building.

Lacking confidence in the recalcitrant-looking elevator, I trudged up three flights before walking into a spacious and well-lit hall with a mezzanine floor. There was a large reception area in the middle. Angled steel book-shelves were arranged along two sides of the hall and all around the mezzanine section.

‘Madam, I want to close my membership,’ I politely informed the lady at the reception who was peering into her computer screen.

She gave me a disinterested glance, asked for my membership card and gave me a form to fill up. I was surprised by her matter-of-fact manner but relieved that no reasons were asked for. In a matter of minutes the formalities were completed and my relationship with the Ernakulam Public Library came to an end. It had lasted all of five months and six days.

It was not a difficult decision.

The library, the oldest in Kerala having been established in 1870, was clearly showing its age. The vast majority of its books were in very poor condition as the blistering summers and humid rainy seasons in Kerala had led to their rapid deterioration. Patronage had dwindled significantly – I didn’t recollect seeing more than a dozen people during my visits – badly impacting their income and coming in the way of retiring and replacing old stock and sprucing up the interiors. The staff were helpful but they wore an air of resignation that mirrored the feeling that one got of an institution in decline.

Some modernization initiatives were visible – an RFID based library management system made the issuing and returning of books a breeze and allowed members to renew books online – but one sensed that the library was engaged in a valiant but losing battle against the twin challenges of a general decline in the reading habit and competition from virtual and brick-and-mortar outlets.

The unhappy condition of the books constrained members to make their book choices only from recent acquisitions. Many of these were in circulation which meant there were just two places worth looking for one’s selections – the large bin where the freshly returned books were placed and the long table at the end of the hall to which they were then transported for sorting. There were elements of curation as well as forced serendipity involved in this process. It resulted in my first two visits being rewarded with some enjoyable picks – Written for Ever: The Best of Civil Lines, the Collected Essays of Arthur Miller and The Oxford India Anthology of Modern Malayalam Literature – books that I was blissfully unaware of and may never have read otherwise.

I drew a blank on my next two visits. I had optimistically enrolled for a class A membership which entitled me to four books at a time but I could find nothing remotely appealing. After a week of reflection I decided that no worthwhile purpose would be served by my continuing to remain a member. It struck me as farcical that my book selection should be reduced to taking pot luck on each visit. The uncomfortable commute and the fact that the place left me feeling dispirited also weighed heavily on my mind.

It was a disappointing end to another attempt to reclaim and relive the pleasant memories I experienced during the 1970s when I was a member and habitual visitor of the British Council Library at Trivandrum.

That was a period when I was finding my studies dry and boring and I longed to read some enjoyable fiction and to learn more about the world beyond what was covered in the local newspapers and magazines. In those days the BCL – as it was known amongst the fraternity – was the go-to place for English language bibliophiles, more so after the closure of the United States Information Service (USIS) library in 1969, and it appeared to be the perfect solution to my woes. There was a waiting list for membership and I remember the thrill I felt when I received my membership card.

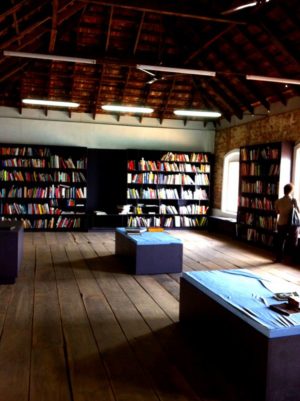

Centrally located, south of the stately Secretariat complex, the library was an elegant, red-tiled, single-storey structure in the spacious YMCA compound. From the tree-shaded entrance gates a short path lined with potted plants led one to a charming portico and then onto a large hall. Originally constructed as an auditorium, the hall was notable for its arches, pillars and high ceilings. This, in combination with the elegant wooden book-shelves that lined the walls and the soft-carpeted floor, gave the library a unique and inviting ambience. It was also impeccably maintained and run with a quiet efficiency and I would feel transported to a different world the moment I stepped in.

Predictably, my reading list was unabashedly escapist – P.G. Wodehouse, Agatha Christie, Alistair MacLean, Richmal Cromption and Frank Richards being some favourites. I found their stories delightful and as they were prolific authors there was always a yet-to-be-read book to look forward to. On rare occasions I would essay reading Krishnamurti or some other philosopher’s work and promptly fall into despondency. At such times Wodehouse was invariably the best antidote.

Equally enjoyable was the time I would spend in the newspapers and periodicals section which was given pride of place in the centre of the hall. There were half a dozen seating clusters comprising low tables and cosy chairs made of cane and wood. This section was well patronised and on a busy day one would have to bide one’s time and move nimbly to secure a coveted chair. I loved the texture of the Sunday Times and would marvel at the mountain of information contained in each issue. My reading of this and other papers was largely confined to the sports pages and headline-grabbing stories. Amongst the magazines my choices included Punch and Autocar but I was as happy to leaf through magazines such as Good Housekeeping simply on account of their outstanding production quality.

When I left Trivandrum, my BCL visits were something I sorely missed. I could, therefore, understand the sentiments of the members when the library finally closed in 2008. There was a genuine sense of loss which prompted the state government to explore plans to keep it running. Sadly, these did not fructify and in 2010 the BCL collection found a new home in the State Central Library at Trivandrum.

During the four decades between my happy BCL days and my recent disappointment at Ernakulam, I mostly satisfied my fiction needs without having to enrol at a library. I was a regular at bookshops of all hues – from iconic names such as the Strand Book Stall in Mumbai, Gangarams in Bengaluru, Landmark in Chennai and the enduring Higginbothams to the modest footpath stalls around Flora Fountain and assorted bookstores at various airports and hotels. During the past decade the overwhelming choice and convenience of Flipkart and Amazon saw me almost completely switch over to online book purchases.

However, the largely impersonal and transactional nature of book buying was a poor substitute for the library experience and from time to time I would get the urge to join one – especially when I was posted at locations where the British Council Library were present. Thus I tried out their branches at Hyderabad, Mumbai and Chennai. The familiarity offered by the layout, procedures and book selections was reassuring but I could never cultivate an affinity with them similar to that I enjoyed with the BCL.

I had an experience of a different kind, though, as a member of the Barbican Library located in the sprawling Barbican Center in London. I had joined the library soon after this performing arts complex had opened in 1982. It was a huge fortress-like concrete structure and a notable example of the Brutalist Architecture in vogue during that period. I would visit the place once in a fortnight taking a brisk lunch-time walk from my office in Cheapside.

I found the Barbican Center overwhelming and would gape in wonder during my initial visits. Negotiating the multilevel design of the building to reach the library was a mental challenge. The library itself was extraordinary in terms of the expanse, variety of book collections and the unique music section. The lunch break was far too short for me to even browse through a single bookshelf. In any case, having caught the English pop music bug I ended up spending almost all my time in the music section selecting CDs which I would listen to and tape once I got back home. The Barbican Library always evoked a “kid in a toy shop” feeling in me but was never a place where I could feel completely at home- I think it had to do with the sheer physicality of the Barbican Centre as well as the cultural adjustments I was in the process of making.

Upon reflection, I have to to say that what makes a library memorable for me is more than the sum total of the size and variety of its collections, the aesthetics and functionality of its design, the attitude of its staff and the quality of its upkeep. It also needs to possess an indefinable attribute that makes it a sanctuary for the mind – making one feel completely at home and allowing free rein to one’s imagination.

I guess I just got lucky with my first library experience although my age and outlook at the time may also have been contributing factors. I suspect it would be wiser for me now to let go of unrealistic expectations.

Old yearnings are perhaps best fulfilled in one’s memories.

Picture from https://tsbookclub.wordpress.com/2014/03/28/the-pepper-house-library/