by Vani Viswanathan

A woman writing is a way of occupying and creating history, says Vani Viswanathan.

‘Things women shouldn’t do:’ (a list that includes)

‘Combing their hair outside the home’

‘Sitting in the verandah when the husband is inside the home’

‘Scolding the husband like one scolds children’

‘Crying frequently – money doesn’t stay in such a household’

I read these half-amused, half-exasperated, when I was at my parents’ place last December. These are from a book Hindu Madha Vivaaham Mattrum Viseshangal [Weddings and Other Special Occasions in Hinduism] , written in Tamil by a grandaunt. The book had detailed descriptions of rituals and processes to follow for key Tamil (Brahmin, perhaps specifically Iyer) functions, ranging from an engagement to a wedding to a ‘baby shower’ to post-pregnancy rituals and the baby’s naming ceremony. The grandaunt wrote the book in her late 70s, it was published by her husband, copies distributed to all women in the family, and then sold to other women for a paltry amount.

On that pleasant, lazy December day, I was reading out lines from the last chapter on ‘Things women shouldn’t do’ and enjoying a good laugh with my mother. She made me check the chapter on the baby shower for a particular reference, and there it was – ‘engage in “couple relations” the night of the baby shower’. We both cracked up. To find this advice, written in a no-nonsense manner in such a book, was really something. “Couple relations” comfortably lived with other sexist advice for women on how to sit or when to oil their hair.

The aunt is no more, but it seemed ripe to write about her writing for this issue, in which we have other contributions that go into the power of women’s voice gained and sustained through words. I have a tee-shirt with the words ‘Women who write occupy history,’ and I wonder if my grand aunt’s little book would qualify as history.

I like the statement ‘Women who write occupy history,’ because it gives us scope to imagine a variety of histories, and how women who write may occupy them. History as a concept hasn’t been fair to women – if anything, it hasn’t been fair to most people other than privileged men. So the stories we read of times before us, of people before us, of rituals and practices and religion that shape our lives, tend to be stories of a limited, privileged group of people. It’s their stories that get written, that get told as the story of our past, the only history.

And when women write, they challenge this idea of one history. They bring up stories hitherto untold, hitherto unheard. They tell stories of lives and thoughts that may be more familiar for more people, simply because men may not have thought of such stories or be able to tell them this way. So the act of women writing is itself a way of occupying history. The stories they tell become a part of histories.

So yes, I think my grandaunt’s book would qualify as history too. Especially because long ago, her husband, my granduncle, told us with a chuckle, ‘She wants to publish her autobiography next.’ The very idea of her writing about her life was funny to him – perhaps it was also about who would want to read that. Besides, he had already “indulged” her by spending a sizeable amount publishing her first book.

I’ve never understood what was funny about that.

Published writing had long been the domain of men, and women have broken into the scene with great difficulty. And still, we have to contend with the likes of VS Naipaul who consider women’s writing “unequal” because of what women write about. After all, what do women have to write about? Their children, their kitchens, their households?

And why isn’t that writing? Why isn’t that history? It is only in recent years that women’s writing, and writing about these topics, have been grudgingly accepted as “serious” writing.

My grandaunt’s book is a compilation of “upper caste” rituals of a small population and by extension a celebration of practices that engender discrimination against not just women of the community but against a substantial section of the population. But it tells me something about her life and her times. Having been raised in the same community, reading her book today shows me how much of the rituals and (some ridiculous) practices I’ve escaped. I wonder what she made of her life that revolved around these practices when she was married off as a girl. I wonder how she became the authority on these practices – what did others tell her that made her think she knew this stuff? Did other women flock to her for advice? I never had the opportunity to ask her these questions, although I remember her as an enterprising woman full of spirit.

So her book is a slice of history for me. Of the lives of some women from times before me, of practices that have disappeared slowly (many for good reason), and of the amount of work that it takes to sustain “culture”, “values” and religion. This is invisible work, nearly-always unpaid, but glorified – because it’s important to the sustenance of (unequal) societal structures.

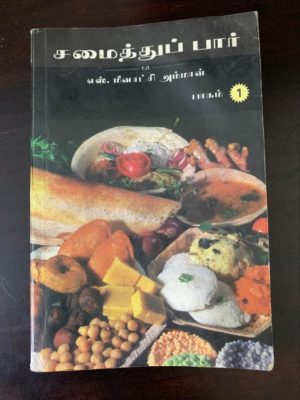

Another book that I admire for the slice of history it offers is Samaithu Paar (“Cook and see,” as they translated it into English) by Meenakshi Ammal. Odes have been written about the brilliant simplicity of her recipes, but I remember two things the most. The measures she used – translated into English as ollocks and litres, which I couldn’t make sense of in today’s world of cups and teaspoons and tablespoons. It took me a few days to realise that the ollocks could be referring to the aazhaaku, a small measuring vessel. The other thing I was struck by was the amount of time that it took to make semiya (vermicelli) and aval (beaten rice flakes) from their raw material. They required a lot of work, sometimes spread over two days to allow for soaking and drying. I imagined women from fifty, sixty years ago, chatting with each other, each one engaged in a different task, making semiya from scratch from wheat to make payasam a few days later.

History is skewed when it doesn’t tell these stories. I’m aware that when I talk about my grandaunt and Meenakshi Ammal, I’m talking about a privileged section of women – women whose families allowed them some level of education, women who weren’t subjected to as much ritualistic humiliation as people from other communities. Among women, it’s such voices that are louder than others. That means there are so many more stories, from women not as privileged, that we haven’t yet found, or that may not even be written yet! Are we, as readers, open to expanding our ideas of histories by finding these stories or reading them?

There is a mindboggling variety of stories in our world. And we need more stories from women to add to this colourful mix. They bring emotions, thoughts, and ideas that haven’t got their due in society. This diversity – a different way of thinking and seeing the world – has the potential to pave the way for a stronger, more equitable, and a kinder world.

Yes, women who write do occupy history.

Vani Viswanathan writes fiction and non-fiction, and works on gender, sexuality and development communications in New Delhi. Her first dedicated foray into writing for the world was when she started a blog in 2005. Her writing typically focuses on the marvellous intricacies and laughable ironies in lives around her. She draws inspiration from cities she’s lived in or visited. Her writing can be accessed on www.vaniviswanathan.com.