by Sudha Nair

The house wore a sombre look, in spite of the fact that Radhika hadn’t made up her mind about it yet. She shuffled across the living room, passing the dining table on her way, absentmindedly flicking an imaginary speck of dust off it, walking over to the window, skimming her hands over the old mull curtains, and pressing them to her bosom.

It was her home, Ganesh’s and hers, though technically now, it was just hers. In the last three months her life had changed so drastically that she was still taking in her new-found freedom and solitariness, feeling alternately guilty with joy and overwhelmed, at being in charge of this huge house and having it all to herself. Her mind dwelled on the soothing evenings spent lately with her neighbour and friend, Devika, under the Ashoka tree in her backyard, having to consult no-one about her decision to eat rotis for dinner or have Appu’s wife cook her some rice. She didn’t have to do one thing or the other, for anyone, anymore. These experiences were still new for her. She did feel lonely at times, but never alone.

She was over sixty, living by herself now, with her faithful help, Appu and his family in the outhouse. Ganesh’s death had opened up a new life to her that even the recent stubbing of her toe and the subsequently diagnosed hairline fracture could not subdue. It wasn’t as if taking care of Ganesh had been a chore, but taking care of an ailing man and being confined to the home at all times does take a toll on one’s mind and body. Folks may have wondered why this widow neither beat her chest nor wailed at her husband’s death, but she couldn’t. She simply wasn’t the melodramatic type. To her, death was a natural conclusion of life. Besides Ganesh had been ailing for quite some time. It gave her peace that he passed on without too much suffering.

The stubbing of her toe had, however, caused quite another unexpected problem. One she hadn’t given much thought to, until now. She had suddenly become Vivek’s concern, and the stubbing of her toe had proved to him somehow that she was incapable of living by herself at her age. Pooh! She rebuked him. She felt far from old and helpless. If anything, she felt reasonably young, and free, completely and utterly free.

But Vivek was insisting that she let Appu go and sell off the house. You should get some rest after all these years, he told her. Not have to worry about taking care of this house. Besides Appa would have wanted me to take care of you. You can hardly afford to maintain this house on Appa’s pension alone. And I’m too far away to visit more often.

She resisted the idea vehemently though she understood what he was hinting at, that the upkeep of this house was a financial burden on him. She could understand that but did it mean that she throw herself on Vivek and her daughter-in-law, Prekshya? No, she hoped it would never come to that, not especially when she was so happy where she was. An uprooting would be painful, quite unthinkable. This was where she belonged, this house passed down from Ganesh’s family. This was her home, hers for the last forty years. This was where Vivek was born.

She let go of the curtains and limped towards the bedroom. Leaning against the old almirah, she caressed its frame, and studied herself in its rust-speckled mirror. The person she saw in it was her, the almirah was hers, and everything in this house was hers. With the sale of the house, nothing would remain hers. She shook her head, shaking away the dreadful thought. She wished Ganesh were still here to calm her down. He would’ve handled this better, she was sure.

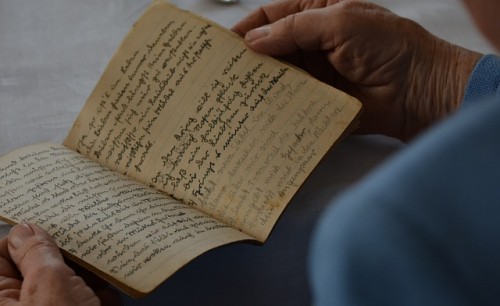

All of a sudden, remembering something, she opened the creaky almirah and reached into its upper compartment. She pulled out a box, settled with it on her bed, undid its latch and pried it wide open. Inside, were her wedding ring, two bangles, the locker key, and some cash. Tucked beneath lay an envelope stamped a long time ago. Nineteen seventy-three, she still remembered.

She’d almost forgotten about its existence until now; it’d been a long time since she’d read it. She edged the envelope out slowly from the box, recognising Ganesh’s loopy writing on the cover, her name spelt out in faded ink. She eased out the letter, and set it on her lap. Gathering her reading glasses from the night stand, she picked up the letter, unfolding it carefully and peering at it like she was reading it for the first time.

Dear Raddy, it began. A lump formed at her throat. No one else called her by that name. Ganesh had been her classmate, later a close friend and slowly her boyfriend, though in those days it would be reasonable to say no such terminology existed, that they merely spent a lot of time together, she helping him with Mathematics and he with her Economics, falling in love unknown to both at the time.

How are you? Before you think I’m doing well let me tell you that I’m not. I feel miserable and lonely and lost. I must have been out of my mind to come to Bombay, leaving everything and everyone behind, especially you.

He’d made her weep with happiness at those words. He’d made no promises before he left but something about the tone of the letter told her he’d wished he had.

The trains here are the hardest to get used to. Every day I struggle to jump in and out. I’m surprised at how people here travel with such ease. I’m squeezed, pushed, elbowed, knuckled, kicked, trampled on…every day. Even after a month, I’m terrified of the travel. I guess I’m just not meant to be in crowded places, trains and buses.

She chuckled, remembering how he shied away from crowds, years later, always preferring hidden spots to touristy places even on their vacations.

I’ve taken up lodging with an old Parsi lady who lives alone in a five bedroom duplex. She’s eighty-five but quite the expert landlady. She lets out individual rooms to working men like me. She has a man Friday and a cook. Every Saturday she treats us to a special dinner with her at her eight-seater dining table. She must have had a large family once. I feel sorry for her on Saturdays like this one when I’m the only one around. Today we had finger-licking roast chicken and cashewnut pulav. She’s an amazing woman, so full of vigour and humour. I miss my mum when I’m around her.

“We can’t let him eat with us,” Radhika remembered her own mom saying. “He’s of a different caste.”

“So what?” she said, snubbing her mom. “He’s my friend.”

“Appa will be furious.”

I wrote you a poem last Sunday. It couldn’t have been a more perfect morning, sunlight streaming in through the straw curtains, making me feel like walking over to your house with a Math problem. You know why I came over with so many questions, don’t you?

She could visualise his smile as he penned that question. She let the letter fall to her knees, took off her glasses and dropped her hands on her lap. She would argue with her mom to let him come to their house every evening. “We’re not doing anything wrong. Why would Appa not approve?”

Amma would be unable to justify Appa’s disapproval but made sure Ganesh left before Appa came home from work by evening.

Radhika picked up the letter again, slid the glasses back on her nose, and read on.

The poem goes like this:

You, only you

Know what it means…

The incongruity of your images

Haunt me in pursuit relentless

Yet meaningless in your absence

The restless soulmate yearns

Beckons you

To stop this futile struggle

Against our true destiny

You, only you

Know what it means…

Forever yours,

The letter had caused quite an upheaval in her heart then. Appa raged with anger when she told him she wanted to marry Ganesh. “You will cease to be our daughter, if you won’t listen to us,” Appa thundered.

She shuddered as the bitter memories swept in. It had the power to shake her up even after all these years. She had gone ahead and married him nevertheless, never regretting her decision for a moment since. “I wish you were here with me, Ganesh,” she cried out softly now.

Ganesh would never have agreed to sell this house. Ganesh often said that this house reminded him so much of his life in Bombay. “It’s exactly like the PG I stayed in. We have more rooms than we need,” he used to say.

It was then that a sudden thought struck her. This house could serve as a PG accommodation just like the Parsi lady’s home. Why hadn’t she considered it until now? It seemed like the perfect solution to all her current troubles.

The idea made her nervous, yet happy. As it opened up her mind to possibilities, a warm glaze spread within her. She’d tell Appu about it in the morning. And ask Vivek to call off his plan. Yes, he would raise issues about safety and the fact that the house needed substantial repair before it could be rented out. But yes, these could be easily dealt with! All she needed was put out a call for young working women new to the city.

The thrill of the new idea sent blood rushing through her veins. She’d manage fine, she just knew it in her heart. With Appu to take care of her tenants and tend to their needs, and Appu’s wife to provide meals, she’d manage pretty well, and earn enough to employ a driver to drive her around. Yes, she needed a driver, so Devika and she could go on their long-overdue temple visits once her toe was healed.

She felt at ease as she reposed on the bed, clutching the letter to her chest. She let out a long sigh as she closed her eyes, and with hope in her heart, drifted into peaceful slumber.