by Archita Suryanarayanan

A train chugged off the platform, hooting shrilly. The porters in red rushed past. A boy feebly tried to sell outdated magazines. A bright voice announced train departures, each number narrated by a different faceless woman making the effect comical and disjointed. Tarun walked wearily to his coach which was at the very end; he was well in time as usual.

He hauled his luggage in and surreptitiously scanned the ages on the passenger list. He was disappointed–everyone in his vicinity seemed above 50. But today it didn’t matter, he sat at the window seat, with a pleasant thrill of anticipation–a seven-hour train journey, a book to read, pleasant climate, green landscapes outside the window.

The coupe was already full, and Tarun mentally named the people in the compartment. The bearded man near the aisle reading The Economist became Dilip Kumar Shah, the lady opposite him, who appeared to be his wife judging by the way her nail-polished feet rested familiarly near his leg, became Malathi Shah.

Tarun glanced at the others – he did not remember when he developed this habit of naming everyone he passed by; he walked down a road and the people around him metamorphosed into Shruthis and Kabirs and Anishas. Though he did not know this, his instincts were often, actually always, wrong – his Shruthi was often Kalpana and Kabir was Ramesh.

The artistic lady next to his Malathi had a powerful personality, he thought, what with the Khadi sari she wore and greying hair tied in a loose bun. She was writing in a little diary and Tarun decided she was writing aplay and named her Mrinalini, omitting the surname as she seemed beyond linguistic groups and communities. The others in the compartment were a fussy couple and their baby, the mother he named Varshini, who was force-feeding the child a banana while the father Arun Kumar watched the remarkable spectacle worriedly, giving his wife instructions if she went too fast.

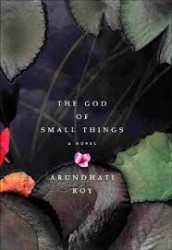

Tarun settled into his seat and took out his book, The God of Small Things. He had tried to read the book when he was in high school and vaguely remembered feeling an odd kinship with the twins, and finding the language intriguing and strangely unsettling. He had abandoned the book midway, being in the phase when he preferred fast paced plots over long intricate descriptions After recently reading an excerpt however, he was captivated and went into a second hand book store the same day and bought a copy.

The copy lay in front of him, smelling of what old books smell of, a small green ink stain on the back cover near the bar code, the cover clearly crumpled like a book read and re-read. He opened the book. In a neat cursive handwriting, it said on the top right–Subhashini R, 16-12-2008.

An image formed in Tarun’s head. A tall girl walking into a bookstore, probably in Calcutta. Browsing through Dickens and Kafka.And finally walking to the billing desk with this book. She held the book to her chest and stepped out of the old bookshop. She walked to her bus stop, the wind blowing her curly hair around her face. She wore a long beige sweater and carried a cloth sling bag with a pattern of elephant. Her feet were encased in bright Rajasthani slippers.

She was probably a literature student, one still idealistic enough to be able to sit on a park bench for hours. Which is where she was heading, in his imagination. She walked past the jogging couples in branded sportswear and the old man walking his dog, the kids in roller-skates and the accompanying mothers exchanging lunch box recipes. She stopped to watch a squirrel scamper past the bushes. She reached an empty bench and sat with her legs crossed, opened the book and took out a green pen from her bag. She wrote her name and the date on the top right corner and held the book back to admire the effect. Then she began reading the book.

He imagined her a few years later, packing up her bags to move from the city. She had books strewn in front of her, and frowned in concentration trying to decide which to take back and which she would have to leave behind. To pick the Somerset Maugham or the O Henry? R K Narayan or Arundathi Roy? Finally she would sort the books into two neat piles. And walk to the store with the pile that had the green-ink-stained The God of Small Things.

She would then maybe move to Bangalore to work in a publishing house. Which would be next to his campus. He would see her everyday when he is returning from the tea shop when she waits at the auto rickshaw stand. He imagined secret glances and unsaid words. One day they would strike up a conversation, and begin sitting in the cafe daily talking for hours. About their favourite books and movies. She would talk about the pain of selling off old books. That is when he would suddenly remember she has the same name as the green-inked scrawl on his copy of The God of Small Things. He would gift her the book the next day, and she would look at the name in pleasant shock. It would be the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

“Ticket, please.”Tarun was shaken out of his reverie. He was back in the train compartment, the book still open on the first page. His co-passengers were looking at him in amusement.

The baby cried. The parents got busy. The lady with the diary went back to writing while the bearded man returned to his Economist. He had forgotten the names he had given them through the course of his imagined story. He sighed. Reality. He opened the book and began reading.

Opposite him, Subhashini watched him as she scribbled into her diary. She saw his dreamy expression and envied his carefree youth. She watched the book, watched how his eyes hovered on the top right corner of the first page. She wrote.

“I can see the green spot. I know it is mine. He has been staring at the name on the first page for the past half hour. I wonder what he is thinking. I can picture the name, the circle over the i, the two lines under my initial. I can imagine the day I got the book as if it was yesterday. The day I got a raise.And walked out of office with a spring in my step and a resolve to splurge on myself for a change. I bought this book, two fountain pens, a new handbag and on a sudden rare whim, a bright printed silk sari that I would wear only once. And of course, toys for my little Anu, she was all I had.

Was it only five years back? When I was happy and content. When the smiling face made me forget all my worries, when the games of Ludo would make me feel light as a child.

This was before my life changed forever, before I went into a daze. Before I knew that the smiling face would not be around for much longer. Before I left the city with half my possessions and left suitcases full of books and clothes ‘accidentally’ in the bus stop. I didn’t want to carry back anything from the city that gave me six beautiful years with my little Anu. I wanted the memories to go away with her. I wanted to start fresh, wanted to start with nothing, since I had nobody.

And now I see the book and I am reminded of the day I returned home laden with the shopping bags and gifts for Anu. The squeals of delight. Feeding each other ice cream. The long game of Tumbling Monkeys that followed. And watching the Lion King DVD for the twentieth time.

It is a happy memory. And surprisingly, I am not saddened today. I feel like sharing my story, after all these years of silence. This young boy with the book seems sensitive and I feel an intangible connection with him because of the book. He might be interested in listening. And I might feel lighter too. I will take the leap today.”

Tarun had closed the book by now. The countryside was making him dreamy and he sat gazing outside the window and thinking of the girl in the sweater. “Excuse me,” said the lady who was writing in the diary. He looked up with a start and found that she was looking at him intently. “Yes?” he asked and smiled. She paused. Her eyes were pained and she seemed to be struggling with her thoughts. Then a mask seemed to fall over her face, and her expression became distant. “No, it’s nothing,” she said, a little sadly. “I thought you were someone else.”

They went back into their own private worlds.

Archita Suryanarayanan is an avid reader and aspiring writer, a student of journalism and an architect. A mixture of opposites, for her, the mundane often becomes magical. She hopes to capture through writing, those fleeting moments that make everything else worth it. Archita blogs at http://thecityrhythm.wordpress.com/