by Paritosh Uttam

[box]Paritosh Uttam tells you about the books he has read through the years, what he thinks are the characteristics of good writing and the authors he admires.[/box] [box type=”bio”]Paritosh Uttam is the author of the novel ‘Dreams in Prussian Blue’, published by Penguin India under its ‘Metro Reads’ series in 2010. Earlier, his short story was published in ‘First Proof: The Penguin Book of New Writing from India 4’ in 2008. Many of Paritosh’s short stories have also appeared in newspapers and print and online magazines. A Pune-based software engineer, he did his graduation from IIT, Madras and post-graduation from IISc, Bangalore. To know more about Paritosh, visit his website http://paritoshuttam.com.[/box]The earliest memory I have of experiencing or anticipating the thrill of reading goes back to my 4th grade. I remember pedalling furiously away from school, rushing home so that I could set my hands on the Secret Seven book, now safely clasped in the bicycle carrier. At that age, we were not allowed to take books out of the school library, but my mother was a teacher in the same school, and so with the librarian’s connivance, I could bend that particular rule. What I distinctly remember from that day almost a quarter of a century ago, is my excitement, my almost-sinful pleasure in the knowledge that soon I could lose myself in devouring the pages of that Enid Blyton book.

I must have started reading much before that, but I don’t remember now the moment I entered the doorway to this wonderful world of books to be lost forever in it. The best idea I ever had was to keep a careful record of the books I read, as though I had a premonition how important a role this harmless hobby would play in my life. It was like Hansel and Gretel dropping breadcrumbs along the way to mark the path they took.

When I grew up, you were initiated into reading, de facto, through Enid Blyton. The world of English children involved in adventure and mysteries became familiar. It never occurred to ask myself what I had in common with the world of The Secret Seven or The Famous Five. With unquestioning faith, I read, accepted and imagined myself in a world where children packed smoked salmon and potted meat sandwiches for picnics, or marmalade and scones for tea. I joined Sue, Jack, Peggy, Julian, George and Timothy the dog in their adventures across castles and moors, tagging along as an invisible companion all the way.

I took it for granted, that through books, you could enter a place and meet people you could not imagine in your real life, but that was all right. Books were magic and it was all right to be taken in by that magic everytime you began reading from Page 1.

In those years, I thought that literature began and ended with Enid Blyton. Anything outside Blyton was not worth reading, by definition.

Then I grew up but Blyton’s characters did not. By my 9th grade, I needed more thrills than what an English picnic could provide. The story of my growing up on my favourite writers and characters happened time and again. Each time, I sincerely believed that what I was reading was what literature was about. As if obsessed, I would read all the books of the favoured writer I could lay my hands on, until eventually and inevitably, I grew bored and found someone else.

Thus, discarding Enid Blyton, I moved on to the more hard hitting adventures of the Hardy Boys, and from there to the cerebral exploits of Hercule Poirot and Sherlock Holmes. Then it was the turn of the more ‘realistic’ international thrillers of Frederick Forsyth, Jeffrey Archer, Arthur Hailey, Sidney Sheldon, Alistair MacLean, et al. Until one day, I picked up a P. G. Wodehouse and realized that literature was not just about mysteries and thrillers. Before Wodehouse, I seriously wondered what would be left for me to read once I had finished the latest Jeffrey Archer release? Had I reached the end of the road of reading?

Around that time, enlightenment dawned. Even if I read and finished a book a day to the end of my life, I would have read only a fraction of all that was worth reading. My tastes opened up, and by the time I graduated from college, I had settled upon the genre of literary fiction as the one that most suited me.

This was fiction that fell in the most conventional definition of literature: writing that deals with the human condition. This definition, not being restricted to a limited set of writers or subjects, has served me well until this day because of the variety and range of writing it encompasses.

I have gone by reputation—books and authors too well-known to be ignored, or by recommended reading lists compiled by experts, or prize-winning books and authors. That way, I try to ensure that I read only well-written books. Even if a book does not appeal to me, it would not be time ill-spent.

Deciding whether a book is well-written or appealing is very subjective. I will lay down the characteristics of good writing that appeal to me.

Foremost, the writer has to establish, very early in the book, that he is in command. That can be done through some remarkable line, or even a turn of phrase, or by some sort of witticism or character delineation, that makes me sit up and think: ‘Wow. This is good. I am in the hands of an expert. Let me sit back and enjoy the ride.’

For me, both form and content—style and story, that is—are equally important. A style is impressive initially, but if I find that it’s more style than substance, I am disappointed. In the same manner, if the book is only story, say, a three-generational family saga, told in a straightforward, linear way, it is not likely to keep me hooked (though I rarely abandon a book unread).

Style need not be conveyed only through the quality of prose, but also be in the way the plot and the narrative are structured. I like to be led back and forth across narrative time, so that I can infer how the past has impacted the present, but this has to be done well to be effective.

Inferring, making the connections between characters and events, is important to me. Too much information being force-fed is the sign of an amateur, while a story where too much is vague and left open to the reader’s interpretation is not satisfying either. The balance has to be right; how much, and where to reveal, so that as a reader, I have the satisfaction of putting things together little by little, as in a jigsaw puzzle, until all the pieces fit in together towards the end.

There are effects that a particular scene or chapter might evoke. But if there’s an overall impact, or effect, the whole book has, that you realize only after turning the last page, that is an even bigger achievement of the writer. If this can be done through a simple style and structure, that to me is the pinnacle of writing. Impact through subtlety is truly worth appreciating.

To take some concrete examples, let me mention a few of the many writers I have read and admired, for different reasons.

V. S. Naipaul for his amazing insight, seriousness, perspicacity, and ability to see the bigger picture. All this, combined with spectacularly taut prose. His style might seem old-fashioned to some, but I love his emphasis on the punctuation with the use of the semicolon and the dash. I prefer his non-fiction to fiction. He is not too strong in plotting in fiction, but when he starts a novel with such a provocative line: ‘The world is what it is. Men who are nothing, or who amount to nothing, have no place in it.’, you know you are in the presence of a master.

Dostoyevsky for his uncanny ability to get into the mind of a deranged or mentally troubled character, to make you think as you are reading the work of a madman. Tolstoy, for his grand sweep of time and place, where the characters literally age before your eyes, very naturally. I like the Russian writers (Chekov included) particularly because their writing is so unaffected, and yet leaves a lasting impression.

Nabokov for his chameleon-like ability to adapt different styles. The opening lines of ‘Lolita’ are guaranteed to get anyone hooked, while his masterly structuring of ‘Pale Fire’ is an experience to be savoured.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez for the ridiculous ease with which he bends time in his narrative.

‘Love in the Time of Cholera’ is a favourite of mine, for the fantastic role the passage of time plays in the novel, and the way it ends—I was half-laughing, half-crying at the tragi-comic ending.

‘The Grapes of Wrath’ by Steinbeck has a beautiful, touching ending. Steinbeck’s dialogues in ‘Of Mice and Men’ struck me for the natural way in which they revealed character of the speakers without needing any explanation by the writer.

Someone like Rushdie in ‘Midnight’s Children’ can carry you along wholly on style. But then you have to be that good at it.

These were only a few of the writers and books that have impressed me. William Faulkner, James Joyce, Thomas Mann, Franz Kafka,… the list is endless.

Earlier, I used to read solely for the sake of the story. Later, as my knowledge grew, I also began to appreciate the writer’s craft in it, and that has made reading a fuller, more enjoyable experience.

I don’t believe there’s any other medium, through which you can experience and understand the lives of people across centuries, cultures, and nationalities to the extent and depth as you can do through the characters of a well-written novel.

The written word holds magic. And when a writer comes along and unharnesses that magic, I am left spellbound.

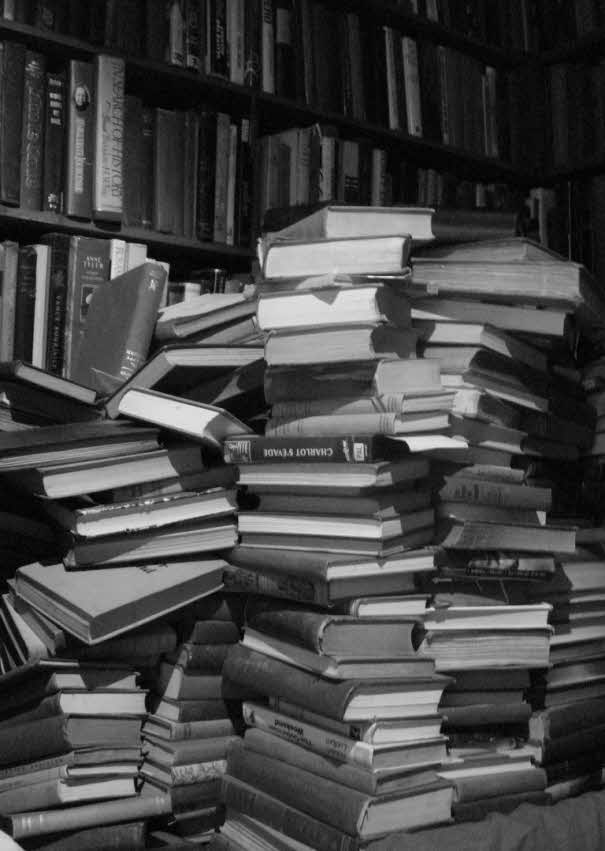

Pic : austinevan – http://www.flickr.com/photos/austinevan/

[facebook]share[/facebook] [retweet]tweet[/retweet]