by Vrushali Haldipur

Balwinder Singh liked following rituals. Every morning he’d rise by 4:30, wash up, grab his pre-made tiffin box of saag and roti, and get ready for work. By 5:30 he was out the door, in Basanti, his yellow cab, his pride and joy, ready to hit the highway.

He didn’t have the time to greet his family, but they were asleep anyway, his wife and teenage son and daughter. He would see them later, maybe on the weekend, maybe not. It didn’t matter, he reasoned. They were stuck in his heart, Fevicol ka majboot bond hai, janaab, tootega nahi, he used to joke back in the old days. These da ys, jokes barely registered.

This morning, things became worse. The sense of guilt that had been creeping up on him all these months had evolved into something heavier, denser, something that he couldn’t quite shake off. When he found himself in the driver’s seat at dawn, he realised he had been completely on autopilot – he had barely any recollection of going through the motions. A cup of joe would clear that, he figured, as he drove up to his regular Dunkin Donuts at the gas station to load up on fuel for himself and Basanti. ‘Bally-ho-ji!’ the coffee guy greeted him, another soul from the desh. Bally-ho-ji didn’t seem to hear. He just took his coffee and went his way.

As he cruised along the BQE, the expressway connecting the boroughs with Manhattan, he couldn’t help think about the phone call from his cousin back in the desh. ‘Balwinder, you know how it is. You have always been our mai-baap,’ his cousin Tejinder had said. Tejinder was like his younger brother – the two had skipped stones across rivers and learned to ride bikes together back home, a long long time ago, in a country far, far away. When Balwinder was scraping together the money to come to the United States more than fifteen years ago, it was Tejinder who sold his cycle to contribute. And today, when Tejinder was in need of money to pay off his medical and hospital bills, Balwinder wanted to lend his support. After all, he was earning in dollars, and he was the eldest in the family.

But fate is a fickle mistress, as they say.

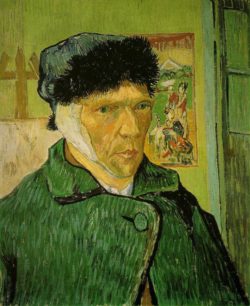

Balwinder had achieved the American Dream, or so it seemed. Soon after landing in JFK airport nearly two decades ago, he made connections with the local Indian community and worked a series of small jobs – as truck loader, garage mechanic, delivery man and so on, till he managed to get a hefty loan to buy a New York Taxi medallion. It was a matter of pride, and a wise investment, because the value of the medallion, then bought at more than half a million dollars, was guaranteed to only go up, given that New Yorkers refused to own cars and preferred taxis to go everywhere. He bought his taxi, which, of course, he had to name Basanti, both for its cheery yellow colour and because like every patriotic desi-at-heart, having grown up on a diet of lassi, paratha and Sholay. He was doing well, working two shifts, then slowing down a bit after marrying the lovely Simran, and leasing out his cab to other taxi drivers for additional income over the weekends.

He had done well for himself, buying a home in Queens, and regularly sending money back home. The motherland, always tugging at his heartstrings, drew him to the community – he always visited the gurudwara all the way in Carteret, New Jersey every Sunday and volunteered at the langar. Life was good.

But time and technology waited for no one, he now thought, as he entered Manhattan. The city was just waking up, everyone in a rush to commute to work – bankers and actors, lawyers and hipsters. He circled a few blocks waiting for someone to hail a cab. As a few emerged from the subway entrance, he was hopeful. Till they started looking into their phones and got into the Toyota that arrived from behind him.

It was the same story every day now.

He was lucky if he made a hundred dollars today. A far cry from the five hundred he was guaranteed in each shift, before the era of the ride-sharing companies. It was the same every day, for the past few years.

He didn’t understand it at first. ‘Why go through the trouble of looking through your phone, typing in your destination, leaving your credit card on their file, and then wait to get a ride, when all you have to do step out and wave to a passing cabbie? Why are they paying someone for all this inconvenience?’ he’d ask his cabbie friends, who laughed it off.

But they too, now, had lost all hope. They’d gather at the gas stations, wondering if the unions would do something to stop the bleeding. Some, like Daljeet, even moonlighted as Rydr drivers in their second shift. ‘Your driver Daljeet speaks 4 languages, has completed 3,000 rides and has 4.5 stars as his approval rating,’ his Rydr profile read. That was it, it had come to drivers seeking approval from riders.

Balwinder resisted going that way, he was too tired. He couldn’t manage working double and triple shifts like he did in his youth. His million-dollar debt was soaring, the value of the taxi medallion had dropped to less than $200,000, and he still had to finance his children’s’ college education and pay off his mortgage – all on a fast diminishing income. He knew he would never be able to repay Tejinder’s kindness nor look after Simran and the kids. And of what use was a man if he couldn’t provide for his own family? The burden of guilt had given him sleepless nights and restless days. It had gone on too long.

He parked his taxi near the East River, downtown. This usually was a taxi-rider’s dream, assured of big-shot bankers going all the way uptown to their homes, with hefty tips. But now it was dotted with folks who kept their heads down and eyes glued to their phones and ride-sharing apps. Just as well, thought Balwinder, as he reached for the gun in his glove compartment. They wouldn’t notice him anyway.

The next day, at ride-sharing company Rydr’s headquarters in SoHo, a bright young public relations executive had a crisis on her plate. ‘Boss,’ she told the CEO, Sean Ross, ‘We need respond to this,’ she said, pointing to the headlines in the New York Post: ‘ANOTHER CABBIE SHOOTS HIMSELF: ARE RYDR & AND CO RESPONSIBLE?’

Ross had been seeing too many such stories recently. It troubled him, gnawed at his heart. He was uncomfortable with the idea that his company had no doubt contributed to this in some way. But was it really his fault, he reasoned. Business was a tough jungle and there were only a few survivors in the race; the rest was collateral damage, he rationalised. Guilt was only for the weak, he believed. But perhaps he could find something of value in this, he thought.

‘It’s good practice to show some sympathy,’ he said to her, ‘But it’s equally important to not acknowledge any guilt over this. We have to be on seen on the right side of this.’

Already plotting a few moves ahead, he said, ‘We could try to extract some benefits from this situation. I say we should use this death as an opportunity for our shareholders. Show a bit of heart – maybe run an empathy-driven marketing or public relations campaign showing that we as a company really care about this issue?’ Pausing for effect, he added, with careful emphasis, ‘After all, the stock market is an emotional being – it loves sentiment and will react positively if we take the responsible lead in this.’

‘But first,’ interjected the PR executive, ‘There’s social media.’

‘Ah yes, of course.’

Ross tweeted, A life lost, not forgotten. We support drivers everywhere. #VRwithU #RydrCares.

Picture from https://www.flickr.com/photos/neeravbhatt/

Very true, this is the plight of taxi drivers now