by Jeevanjyoti Chakraborty

[box]Are you a master of the English language but someone who struggles with the native tongue? Then here’s something you should read. Jeevanjyoti Chakraborty explores a relationship of a different order – his relationship with his mother tongue.[/box]There comes a time in the lifespan of every generation when they are expected to take centre-stage. Get a grip on the helm of the proceedings. In these times performers emerge. Brilliant, peerless, set on the highway to immortality. Non-performers languish. Pseudo performers fade quietly, not discontentedly perhaps, into everyday oblivion. And somewhere in between, normal, regular men and women engaged in routine jobs, fitting cog-like in the machinery of the society, keep shining softly. It is they who define the zeitgeist. Their ethics renew morality. Their language becomes the grammar. And, it is their opinion that gets translated into the voices of mandate; even more trenchantly into the vetoes of sanction. So, when these men and women point out, with an uncomfortable regularity, your handicaps due to a detachment from your mother tongue, the message gets driven home. Hard.

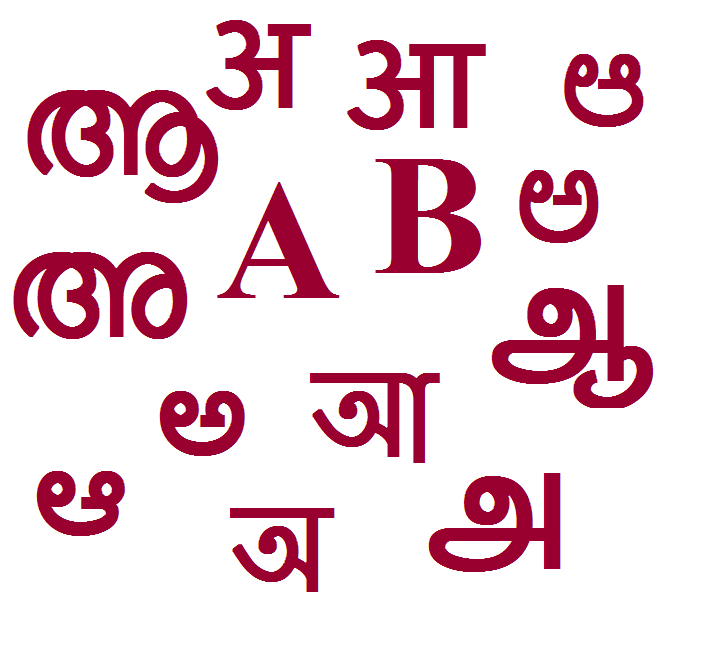

The realization sets in that the ride which had seemed to be all hunky-dory has no return ticket. The ride – the mad ride – to master the lingua franca; starting way back with those days when the first alphabet learned was the Queen’s and not the mother’s (or the father’s), followed by a slow, patient and fundamentally strong build-up to a stage where the first big lessons started being taught. Efforts exerted in reverent response to expectations ensured that each step along the way had been landed upon with a firm footing, and that heights reached would be kept and built upon further. And build they did – for soon enough, the works of the Grand Masters started appearing. The ground work was ready, the seeds were sown. And like sweet rain came Shakespeare, Dickens, Keats and Company descending from the heavens to nurture the well-laid seeds. Add to that, the timing of the first peeks into adulthood and the exhilarations of a blooming mental fecundity, and you had a heady concoction that churned love’s labour into a frenzied whirlpool of pious worship.

Along the way, the native alphabet was introduced. At that point, it seemed funny somehow. Care was invested in measured precise proportions of the bare minimum dictated by necessity. Expectations seemed low enough. Exertions were kept even lower. Not only didn’t it seem important enough, it became the Nemesis of Percentage. So, forget labour, forget love, the native tongue became the villain in the immediate scheme of things. Forget even the funny bit. It had become a thing to go up against – loathed and detested. The ground work for a stunted growth had been laid. Nice and rock solid.

Yet, it was not so much the mandatory bindings of the school curriculum that fed this unhealthy growth as it was a misguided mentality – a mentality emanating from a strange perception fuelled in no small measure by the mighty diktats of petty views, slavishness and hypocrisy; a mentality that perversely converted the need for proficiency in the lingua franca as an automatic green signal to immerse oneself in the discipline of reaching one’s higher self through the path of the adopted word. The native language was reduced to a baggage that had to be tagged along. You had to become great inspite of your mother tongue. In such self-defined situations, there seemed to be some credit in creating an aura of insularity from one’s own language.

And so, the mad rush to master some ill-defined art of self-improvement had come at the precious price of complete detachment from the mother tongue. That price was not of an education designed with practical needs in mind. Rather, it was the price of arrant foolishness.

Ridicule from sagely men and women elicits but only the impish smile.However, ridicule from the shining men and women defining the zeitgeist somehow prick. Epiphanies need not strike out of the blue; they may start like a steady roll from behind the veiled darkness and then conjured as if by some magician percussionist, start rising in a crescendo until that vague soft metronome becomes a pounding pulsating beat which enthralls you, and then starts swaying you with a hold that you just cannot shake off. It is then that perceptions change.

While arrant foolishness might not get replaced overnight by solemn wisdom, a realization of one’s own foolishness and naïveté must certainly be deemed borne worthy of a second-hand imposed epiphany. Perhaps not entirely imposed (by ridicule, that is) either, because for some time there had been a nagging feeling that something didn’t feel alright because it felt so warm and curiously blissful to read (albeit, with some difficulty) good pieces of literature of one’s language. There had hardly been any training to appreciate this. It was too easy to pass this off as a more mature understanding. It felt as if the history of my descent, captured in my genes, was revolting against a lifetime of alienation, through the strange response of a homely groovy sweetness. But those initial moments of sweetness started getting marred through more unpleasant honest realizations.

Nowadays, when I see men and women of my age boldly taking the stage and speaking loud and clear, enunciating the dulcet notes of my language, I feel jealous. I wish I could do that too. Playful ridicule during informal conversations leads to nagging feelings of shame. The handicap itself has started to feel stifling and painful. I have made a conscious attempt to overcome that handicap and each time the lack of proper training has stymied my efforts. I decipher a sentence, then another and finally earn a paragraph to my credit, and it feels great! But, my own limitations rise up in vengeance. The whole process is excruciatingly laborious. I want, with all my heart, to read and enjoy the great works of my native language. But I stand helpless under the weight of my inability. This is a thirst that will not be quenched. I have even tried to pull off the stunt of trying my hand at native literature armed with little better than a chip on my shoulder. The result has been that the chip only broke in deeper. The detachment has grown too deep. The insularity has percolated into my marrows. And the bitter truth is that I will always remain the stepchild of my own mother tongue.

I cannot help it. But, amidst all the complexes of incompleteness, I feel the old slavishness and the hypocrisy melting away. I thank God that now I have at least started feeling the shame! And, I also thank God that I have started feeling the pain!

After a lifetime of rootlessness, I can feel the earth beneath my feet again. The shame and the pain will always accompany the stepchild. But there is pride in this new-found shame and comfort in the pain.

[facebook]share[/facebook] [retweet]tweet[/retweet]