by Vaishnavi Rajendran

The rain came down in sheets as the double-decker groaned its way through the traffic. As was usual at this time of the morning, the bus was packed to the gills, as an unending sea of humanity rushed in and out, the blues of a soggy London Monday hanging palpably around the denizens of Battersea.

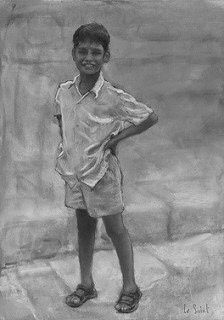

Taking my granddaughter Kiki to school was something that I looked forward to everyday, my time with her that I selfishly hoarded. We sit at the back of the bus and Kiki usually has her nose buried in a comic book while I give way to the deluge of memories that await to flood my brain every morning. And so I look back, sometimes voluntarily, but more often than not, as some sort of a well-oiled muscle memory that finds its traction in the simple act of taking Kiki to school; her brightly coloured school binders and Hello Kitty pencil kits and tennis shoes taking me back fifty odd years when I was a scrawny schoolboy with a muddy cloth-bag and a spit-spiffed black slate.

I was born in a small village near Madurai, a land so aptly and beautifully described by Bharathiraja in his movies. Dry and arid, the land and its people both display a tensile strength and timeless grace I have seen repeatedly in my life. And the person that I have been recalling a lot of late, eddying in the currents of my past, a person who embodied a hefty share of those qualities is my old headmaster, Karuppaiah Vathiyar (teacher) as he was known. In the decades since I left Virattipathu, a lot of my memories have blurred in and out in sepia toned snapshots but him I remember with an uncanny clarity that has belied the decades.

My school was a ten-minute walk from our house and the scorching mornings would find a small gaggle of boys and girls making their way to class, with shiny well-oiled pates and holy-ash drawn across knobby foreheads. And there he would stand, near the mud road that saw the odd lorry or car trundling past but mostly had bullock carts or horse-drawn carriages hurrying along. He was not a tall man; of middling height and ever so slightly rotund, he nevertheless had a patrician air about him that was accented by the simple white, homespun shirt and veshti he wore, the only kind of clothes that we children had ever seen him in.

He would stand next to that highway, the hem of his veshti flirting with the red dust, his head flung back and his eyes on the teeming streets on the other side of the road. We children always scrambled to make that last stretch across the road down to the school yard and building beyond in as decorous as a file as possible, weighed down as we were with that austere gaze upon us. Growing up, I had always assumed that he stationed himself there by the mouth of the school yard every morning to discourage tardiness and catch any stragglers but I realise now that it was simply to oversee that none of us children got underfoot of all the messy traffic that began on that dirt road at an early hour.

He never made eye contact with any of us, his eyes always on the road. Only his intermittent nods to a repeated chorus of “Vanakkam Aiiya!” as children filed past him gave us any sign of acknowledgement on his part. Apart from presiding over the school, Karuppaiah Vathiyar taught just one subject, Tamil. His English was simple, unadorned and to the point but his Tamil was a thing of beauty. During class hours, the austere headmaster transitioned seamlessly into a beguiling storyteller, effortlessly evoking images of kingdoms past and the rich fabric of Tamilian literary history; of a blue-skinned prince in exile, of a lad who died on a riverbank with the Indian flag upon his chest, of the Mahakavi’s call for fearlessness and his impassioned love for the eponymous Kannamma; of a scorned maiden who once made the fabled city of Madurai go up in flames.

Karuppaiah Vathiyar was not a wealthy man; he had rarely left Madurai all his life. He was just a simple school teacher who defied the social norms of the day by opening a school on the proverbial wrong side of the tracks for the children of lower caste families who could neither afford nor were given admission in the other bigger schools in the area. Never one for societal mores, any respect that he wrested from the rigid society of our little village was hard won. Harking back to those days and with the wisdom of my own life’s experiences, I can only guess at the insurmountable odds he must have bested again and again to keep that school running.

He was perhaps the first person in that village that drove home to everyone the fact that even the luxury of simple times could be afforded only by the rich and the entitled. The coolies and the labourers; the farmhands, the scavengers; the working class of post British era India, the complexity of whose “simple” lives exposed the country’s ugly feudal underbelly, was still caught in a death grapple for dignity. Karuppaiah Vathiyar gave the people of his village that dignity. He ceaselessly urged the poor parents of the area to send their children to his school. I still remember him making the rounds to households that had forced their boys and girls to drop out citing reasons of poverty, puberty or whatever it is that makes parents of little means to devoid themselves of hope for their children.

I understand now that his was mainly a thankless job, confronted as he was by tired, ignorant parents who had neither the strength nor the foresight to see the reality of the future he was trying to conscript them into. He never gave up though – and through good days and bad, through alarming numbers of children dropping out and through every child that could successfully finish school, he kept it running. He did what he did without fanfare, doling out lessons and scolds in equal measure, reiterating that while even meagre daily wages would indeed help our families, if we got an education, it would help them more. That we, whose spines had bent from generations of servitude finally had a chance with a new India and that we needed to take it with everything that we had.

Karuppaiah Vathiyar was not a pedlar of dreams; he was a pedlar of futures. I eventually moved away from the little village I was born in and worked my way towards a living in Chennai, the pattanam (city) that my own parents had always dreamed of. In those immediate years, caught up in the painfully robust affair of living life, I didn’t give much thought to my village or that old school or the headmaster to whom I owed my future.

The older I grew, and the more introspective I got, I was conscious of a vague sense of regret for cutting myself off from the scenes and sites of my boyhood completely, but life, as they say, took over. It is what it is and in dealing with the cards we are dealt we perhaps forget the essence of the more that we could be.

Through the years, Karuppaiah Vathiyar slipped in and out of my thoughts, and I grew to be profoundly thankful to him, watching my own children take root and flourish with an ease that I never had. An old man’s foolish fancy perhaps but I would like to think that – entirely subconsciously – I have at least attempted to have something of my erstwhile headmaster in me while dealing with the debris of adult life: his quiet grace, the compactness of his thoughts, the rigid control he had over what we knew to be a formidable temper, his unshaken conviction in every human being’s right to happiness and dignity. Karuppaiah Vathiyar heard his children and he took them seriously: their antics and their silences, their tears, their dreams and their fears, and their souls that beat behind their vulnerable eyelids. No child was too little for his attention and no mistake too great not to be forgiven. Even in his insistent adherence to rules, he was perhaps not what we children might have wanted at that time, but he was what we needed.

Regrettably, I never did act on my unspoken intentions of getting in touch with him, if for nothing else but to tell him that I owed him a little bit of everything good that had happened in my adult life. Years passed and the last I heard, he had passed away; to the last, he had been a beloved old patriarch in that village and one who was mourned greatly. I had missed my chance through nobody’s fault but my own, and that was that.

Now in the twilight of my life, in taking Kiki to school, I am once more reminded of Karuppaiah Vathiyar and the life that I and many like me dared aspire to because he took a chance on us when nobody else wanted to. He continues to live on in children like Kiki and in the endless expanse of time that spans three generations and a boy’s journey from a tired old village to a snub-nosed little girl who has thankfully never had to question the necessities in her life.