1) To begin with, for the benefit of those who may not be well-acquainted with film criticism, could you tell us what, if any, is the “purpose” of a critic? Is the film critic a guide? A rating-giver? Or is criticism to be kept in the category of “art for art’s sake?”

I go back to the story of the blind men and the elephant, with each man touching a different part of the elephant (tusk, trunk, tail, leg, body) and being able to talk authoritatively only about that part. We are all similarly blind when it comes to art. We are equipped – due to various social factors and personal biases – to see a film in one way, and I think the critic’s job is to explain that one way: what he thinks of the film, and why he feels that way. So, obviously, a critic can never be a guide to a large number of people. And his ratings will be largely useless. But if the critic is perceptive, then you can come away learning a lot about the tusk and the tail even if you touched only the trunk. The critic, essentially, helps you see a film a certain way. Whether that way has any value, personally, is something the reader or audience has to decide.

2) Unfortunately, reviewers get little space in mainstream Indian media to write lengthy, engaging pieces about movies. By this, we refer not just to the weekly reviews that rates movies by giving them stars, but also, in general to the paucity of space in Indian newspapers or magazines for cultural and cinematic criticism. In fact, good reviewers have had to resort to blogs or personal websites to publish their detailed reviews. Under such circumstances, how do you think the craft of long form reviewing will survive?

The answer is right there in the question. Blogs offer unlimited space. If you really want to talk about a film at length, there’s nothing stopping you. Of course, the longer the review is, the lesser the readership – but that’s a call the critic has to take.

3) There is a tendency to compartmentalise films based on their genres. So a movie that deals with social issues is deemed to be better than one that deals with vampires. What are your thoughts on this, especially since not all of that compartmentalisation is unwarranted: many out-and-out commercial movies do dish out liberal doses of formulaic and predictable plots, forcing the “thinking man/woman” to turn to other directors. (We mean dropping Michael Bay in favour of Richard Linklater!)

A film is good if it does well what it sets out to do. I routinely get flak for praising B-movies and being hard on films with “noble themes” – but if the B-movie wants to be a B-movie and it does a good job of being a B-movie, then it’s a success.

4) In a country like India, where women are still oppressed, minorities are continually harassed, human rights are violated more often than not, do you think it’s important for critics to trash movies[1] that are sexist, misogynist or stereotype-propagating? By extension, can, and should, a critic try to shape public thinking?

No. It is important to take note of these things and hold the filmmaker accountable, but the aspect of cinema comes before everything else – before even the aspect of society. The critic’s job, in my opinion, is to talk about the film as a piece of cinema rather than as a piece of society. Of course, it’s impossible to do this completely – but what I am against is the “shaping public thinking” thing. If a critic should shape anything at all, it’s the cinematic lens of the reader, helping him or her see films in a more engaged manner and rejecting the notion of directorial authorship in favour of personal readings.

5) What is your opinion of reviewing in India? Is there a scope for it to be better?

Of course it can be better. But three things constantly work against this. (1) The space, in the case of the print medium (or the screen time, in the case of television). (2) This need to be the first person out with a review, which means that you barely have any time to process the film, turn it over in your head, before you start writing about it. (3) The need to be seen as witty etc. so that your snark gets widely retweeted… Sometimes this makes analysis impossible.

6) Which reviewers, in India and abroad, do you read? Did you have any favourites (like Pauline Kael) when you started reviewing?

I read all the critics who are considered “top critics” (in Rotten Tomatoes’ parlance). I stay away from reading anything till I’ve written my piece (though this is becoming increasingly difficult, as a line or two from someone’s review may end up on your Facebook wall or whatever) – but after I’m done, I go to the review aggregators and see what people have said about the film.

7) Let’s talk specifically about Tamil cinema. The landscape of this industry has been changing and evolving more rapidly than ever before – among many other changes, there are newer mediums (short films), newer actors, more ‘local’ storylines, and perhaps lesser heroism than earlier. What do you, as a reviewer, feel is heartening about Tamil cinema today? What about it do you find disheartening?

The heartening thing is that young filmmakers with a vision are able to bring off their films without compromise. The other side is that this still isn’t a very professional industry, which means, for instance, that the producer of a film can take a call on changing its release date without informing the director (this happened recently in the case of Jigarthanda). But yes, things are looking good in Tamil cinema.

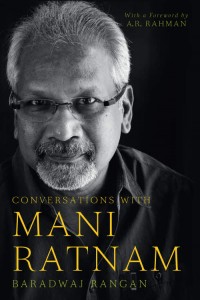

8) While we are discussing Tamil cinema, this interview cannot be complete without a question on the book you authored. ‘Conversations with Mani Ratnam’, evidently, is a dream come true for you. Writing this book on the works of one of the iconic directors that India has produced would have been an intensely gratifying and an unforgettable personal experience for you. Now that it’s been about two years since the book came out, what is it that pleasantly haunts you about the experience of conversing with Mani Ratnam as well as writing the book?

you authored. ‘Conversations with Mani Ratnam’, evidently, is a dream come true for you. Writing this book on the works of one of the iconic directors that India has produced would have been an intensely gratifying and an unforgettable personal experience for you. Now that it’s been about two years since the book came out, what is it that pleasantly haunts you about the experience of conversing with Mani Ratnam as well as writing the book?

There’s a part in the book where he says he cannot watch any film of his for more than five minutes, because after that he sees only the mistakes. I think any piece of writing is like that for a writer. There’s so much more that could have been done. I am reasonably happy about the book, and the experience with the conversations was great. But what makes me really happy is the response of some readers who say “I didn’t know there was so much involved in the making of a movie.” To have been a small part of someone beginning to see movies in a whole new way has been the best part of the exercise.

9) Finally, we do understand that lists tend to leave out more than they subsume, but we couldn’t resist asking – could you list ten of your favourite films (across languages)?

This is just impossible. But some favourites include Duck Soup, The Story of Adele H, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, The Conversation, AI: Artificial Intelligence, Barry Lyndon, The Terminator, and when it comes to Indian films, Mother India, Navrang, Stree, Sholay, Kannathil Muthamittal, Mughal-Azam, Dil Se, Avargal, Thappu Thalangal, Uthiri Pookkal, Mann Vaasanai, Nayak, Ghare Baire…

Interview by Yayaati Joshi, with additional inputs from Anupama Krishnakumar & Vani Viswanathan

A pretty concise interview. Did not know that Jigarthanda too had its fair share of controversies.

Enjoyed the questions and answers equally! Looking forward to reading the book on Mani Ratnam.