by Ajay Patri

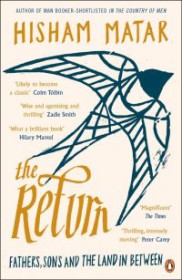

I read an article a few weeks ago, a compendium of the best books of 2016, as selected by well-known authors. In this list, the book that several authors, including Julian Barnes and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, had selected was The Return. I was intrigued by this level of acclaim. I must admit that I hadn’t read any works by Hisham Matar before, even though I had read somewhere that his first book, In The Country Of Men, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize a decade ago. Therefore, my reading of The Return was a foray into uncharted territory.

The Return is a memoir about several things. It’s an account of the kidnapping of the author’s father during the reign of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya and the subsequent search for details about his incarceration. It’s also an account of the author’s return to his homeland in 2012 after years of living abroad in exile. It weaves together these two distinct narratives, spanning over two decades, with glimpses into the colonial past of Libya itself.

If this feels like an overly complicated exercise, then one would be underestimating the dexterity with which Matar handles his words. As a reader, I never felt that I was cast adrift, nor was I confused by the multiple timelines, events or people. This clear-eyed narration is one of the biggest strengths of the book; the literary equivalent of jumping from one boat to another without wobbling or getting your head caught in a spell of dizziness.

At the heart of memoir is the relationship between Matar and his father, Jaballa. The senior Matar was a diplomat in the years before Gaddafi’s coup and later, one of the most vocal dissidents of the dictatorship. He was kidnapped from Egypt in 1990, when the author was nineteen years old. As the blurb points out without any embellishment, the author never saw him again. But he’s present throughout the memoir, sometimes in fondly remembered memories from childhood where he’s reciting poetry at dinner parties, or reading banned books during their years of exile or having conversations with the author and his brother while they are all stretched out on a narrow bed (the familiarity of this image, of a family at ease with each other, is both sweet and indescribably sad, knowing what comes later). On other occasions, he’s present in the elegiac and emotional passages that paint the author’s yearning for him after his disappearance. There is grace in the way Matar handles these intensely personal introspections, a delicate task given that these passages are often the most heart-breaking in the memoir and could easily have slipped into melodramatic territory. Instead, you have understated gems such as this: ‘There is a moment when you realise that you and your parent are not the same person, and it usually occurs when you are both consumed by a similar passion.’

This reference to their shared passion brings in the larger story being told in the memoir, that of the author’s return to Libya after the fall of Gaddafi following the Arab Spring revolts in the country. Matar campaigned for years against the dictatorial regime and his works of fiction are also written in the backdrop of the atrocities committed by it. His return, therefore, feels symbolic of change, of an acceptance of dissent when there was no space for it before. It also coincides with his meeting several relatives, uncles and aunts and cousins, people he hadn’t seen since childhood. Many of them had spent a large chunk of their lives in prison without due process of law justifying their incarceration. Matar recounts his own efforts at trying to get them released before the fall of the regime but as he notes, freedom for them isn’t a cause to celebrate; it is, in many ways, a time to mourn the years lost rotting away in a small cell. The memoir doesn’t shy away from the guilt that seems inevitable in such a scenario; Matar is mindful of the freedom he enjoyed while his relatives were jailed, and the distance this engenders between them.

An even more overarching tale, one that neatly encapsulates the Matar’s personal journey, is that of the country itself. For the ignorant and the uninformed, and I would count myself in this category, the memoir serves as an excellent introduction to the history of Libya, from the oppression it suffered under Italian colonial rule, the brief period of growth it enjoyed after independence before being subjugated again by a capricious man for the better part of half a century. This is particularly poignant for a reader living in India, where the imprints of our own colonial past are all too evident. This connection breeds empathy, a reaching out across continents and time zones. It also led to a perverse happiness in knowing my own country is a democratic, albeit one where we often take our freedom for granted. To read about the experiences of someone grappling with what ought to be the natural order of things is a humbling experience. What makes the memoir even more disquieting to read is its topical nature; the events described happened in the recent past, and similar instances are unfolding in other places. Syria comes to mind, a county embroiled in a bloody conflict against a despotic ruler where the lives of innocent people are being destroyed on a daily basis.

If this realisation sparks outrage against those who stoop low in their quest for unbridled power, it also emphasises the need to fight injustice when one sees it. Matar’s consternation is not just directed at the regime, but also those who passively stood by and let the human rights violations occur and sometimes, even worse, let commercial reasons justify their inaction. He is particularly scathing of British government, including the former Prime Minister Tony Blair, for their agenda of appeasement with Libya for the dividends it would pay off, mainly in the form of imports of oil.

While this moral indignation at the politics played by those in power is palpable, it is not the focus of the book. The memoir works at its incendiary best when its focused on the personal, either of Matar’s own journey or the brief interludes in which the journeys of others are examined, including a cousin who fought as a revolutionary during the revolt and was killed by government forces, and an uncle who spent years in prison and found that his children, mere toddlers when he was jailed, had all grown up by the time he was released.

These stories are often all that remain of these individuals and they highlight better than anything else the human cost involved in such bitter fights for survival and freedom. That Matar does this with simple prose that is nevertheless powerful and immaculate is what makes his book a truly unique read.