by Hari Ravikumar

Alan Jones, drunk, haggard, bankrupt, frustrated and on the threshold of depression sat himself down near the fireplace with a half-empty bottle and a vacant expression. At 51, he had lost practically everything. Except for his father’s house, which he inhabited, and a few pieces of furniture, everything else was sold. Yet he was wading in debt. After some moments of despair and self-pity, he decided to search the attic to see if he would find something of value. It would at least buy him a drop of whiskey.

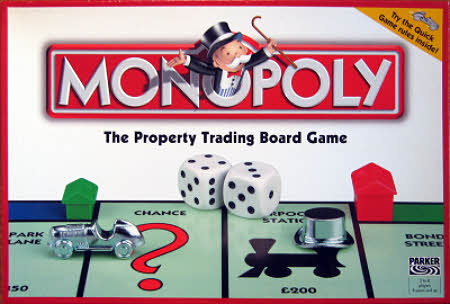

The attic was dark and dusty but that did not deter him. He groped around with the help of his mobile phone torch for a few fruitless minutes. Then his eyes fell on the worn-out cardboard box cover of Monopoly, a board game that he and his sister used to play for hours together during their winter break. The nostalgia abruptly halted his search for something of material value. Within a few minutes, having dusted the top of the box, he was sitting in front of the fireplace, ready for a careful examination of the contents of the box. Right on top was the game board, with its numerous locations in London, all waiting to be bought and rented. The colours had faded away but not his memories: the constant struggle to buy train stations and important locations, the prayers to stay out of jail and get a good card at Community chest or Chance, the squabble with the rolling of the dice.

He put the game board aside and then opened the small case that contained all the cards – the Chance cards, Community chest cards and all the Title deeds for the various properties. Wrapped in a transparent cover were the pieces, the dice and all the miniature hotel pieces. Finally, he opened a valise which contained all the money. He took out the notes and held it in his hands. When he saw the notes, the effect of the alcohol was suddenly nullified and he was wide awake. The money from this tattered, forgotten 1967 edition of Monopoly was surprisingly real. It looked and felt like real sterling pound. He pulled out all the notes from the valise and counted it. He found some twelve thousand pounds. He rubbed his eyes and pinched himself to confirm that he was not dreaming. 12000 quid, out of nowhere.

Suddenly something struck him and in minutes he was darting across chilly London. After much labour he reached his sister’s house in Dartford. It was half past eleven and his sister was almost asleep and she snapped at him for this unearthly-hour intrusion. He apologized and mumbled something but soon lost strength and sat down on the pavement. She pulled him up and dragged him inside.

“Alan! Look at you. What the hell is wrong with you? If Peter sees you here, he’s going to drive you away. What do you want?”

“Alice, please can I ask you a favour?”

“Don’t ask me for money. I’m not going to give you any.”

“No, no, not money. I want your old Monopoly set.”

“What?”

“You remember that board game Monopoly? When dad bought one home, I insisted that it was mine, so he bought you one, but you would always make me use my set. Remember? Can you give your set to me?”

“Have you lost your mind?”

“Please. I need that. Now!”

“Don’t be thick, Alan!”

“Please Alice, please.”

“I have no clue where it is. Must be in the attic. I’ll ask Peter to find it during the weekend and send it over.”

“Please can I just have it now? I will go and look for it in the attic and I will take it myself. I won’t touch a thing, I promise. Please, Alice.”

“This is the limit. You’re such a blockhead. Fine, go! And don’t make a sound – Peter might wake. Go and fetch it quick for Christ’s sake. Wait, let me give you a torch.”

Seventeen minutes later, Jones was scurrying back home with the desired box tucked under his arm. It was past midnight when he reached and he sat down in the same place in front of his fireplace and carefully opened the box. He knew exactly what he was looking for and he was not disappointed. He found a wad of notes that amounted to about fifteen thousand pounds. 27000 quid in all. He hadn’t seen so much money together in a long time. During the days he was a successful businessman, he rolled in money but things were different after his partner left him, sans capital, and left it to him to run the show on his own.

The next afternoon, he had half a mind to take the money and get himself a drink. But something inside him made him grateful for this miracle and he vowed never to get drunk again. Instead, he stared planning.

Within a week, Jones had visited all his old schoolmates whose addresses he still had with him, and in the guise of collecting old board games for charity, he had appropriated all their Monopoly sets. And in every one of them, he found real money. He had over a hundred thousand pounds now.

He slowly started investing in small properties in Old Kent Road, just like he used to do in the old days when he played with his sister. Within a few years, had holdings in Pall Mall, Strand, Trafalgar Square and Piccadilly. A few more years later, he was owner of a small hotel near Marylebone Station, a few shops in Bond Street and a house in Park Lane. Six years after that incredible night of coming upon the riches in his attic, he bought a corporate office in Mayfair. He was one of the wealthiest in all of London and seemed to get richer all the time. A few months later, the government announced that Alan Jones, the great real estate baron would be made Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, and amid much fanfare, Jones was now Sir Alan Jones, KBE.

One Sunday afternoon, sitting at home with his newest girlfriend and playing around with wads of currency notes, Sir Alan picked up a £1 note and held it up to the light to see it better. To his shock, it resembled the old Monopoly bills. He looked around at all the notes that were strewn around the house and found bills in orange and beige and yellow and white. All his money had turned back into Monopoly money. The girlfriend gave a shriek and ran out of his house, for good.

It took him a while to digest the horrible turn of events and when he finally recovered, he ran to the nearest ATM and drew out money. Real money. He saw it, touched it, felt it and ensured everything was in order. He was quite hungry and went to a nearby restaurant to get a meal. After finishing his meal, he took out the money to pay the bill but he found only Monopoly money in his pocket. He gave his Credit card instead but that wouldn’t work. He gave his Debit card and that wouldn’t work. Helpless and hassled, he mumbled an apology to the manager who had by then recognized him and let him go.

Over the next few days, he drew out a lot of cash from all his bank accounts and the moment he tried to use it, it turned to fake bills of the Monopoly game. All his Credit cards had become Chance cards and his Debit cards became Community chest cards. He started living and dining at his own hotel near Marylebone Station. He had properties all over town but all his rent was fetching him nothing; it was utterly useless lying in the bank and as soon as he converted the money into currency, it would get converted into fake bills.

A few weeks after this horrible turn of events, there was an onset of winter in London, and one frosty night, after downing many bottles of booze, Sir Alan decided to visit his father’s house. It was on such a wintry night seven years back that his fortunes had shined.

Sir Alan, drunk, haggard, bankrupt, frustrated and on the threshold of depression sat down near the unlit fireplace with a half-empty bottle and a vacant expression. At 58, he owned so much but truly had so little. Reflecting on the past seven years of his life, he gave a low growl and decided to search the damned attic once again, to see if he would really find something of value.

He lit a candle and fumbled about in the dust and darkness for a while; in a corner he came across his old ecology book. While at school, it had been his favourite. He opened the first page of the book and held it against the dull candlelight and read the words written on it in a child’s handwriting. It was a Cree Indian proverb he had learnt on the first day of class. “Only when the last tree has died, the last river has been poisoned and the last fish has been caught, will we realize that we cannot eat money.”