by Preeti Madhusudhan

Having set out in the quest for the perfect love – that displayed by the Azhvar Kaliyan towards The Lord – we had covered a few thousand miles from Sydney suburbs to the rural hamlets of Tamil Nadu. Starting from Kumbakonam, we have gone on a spiritual trail covering the various temples and their lords that he sang of. Our trail, we soon discover, includes places which commanded his supreme attention, sites that witnessed the completion in the evolution of the Azhvar in terms of poetical and devotional maturity. As though from the outward spirals, we move towards the centre of this trail , to his origins. The intensity in eagerness of us travellers is akin to frenzy now.

On our way to Tiruvali, his birthplace, we mull over the life of this tribal chieftain, Kaliyan. In one of the earliest poems of his magnum opus, Tirumozhi, the Azhvar says of the Lord:

My master my parent my consummate worldly relation

My liege my divine possessor

He goes on in the same decade to state that the Lord is more compassionate than one’s mother who gave one life. This is the state of mind of the Azhvar, once he has received enlightenment through divine intervention. It is to Tirvali, the place that bore witness to the said event, that we venture thence from Nagapattinam, where we were last drenched in the poetic verses of the Azhvar.

We take a brief detour at Tirukkannangudi, where we hear the tales of the mischief and religious fervour of the Azhvar that still have the Buddhist historians talk of him in hushed tones. They raise their eyebrows in disdain, tut-tutting their tongues, shaking their heads thinking of what could have been, had it not been for Tirumangaiazhwar’s intervention. Here’s the tale. There seems to have existed in Nagapattinam a Buddha vihara with a golden statue of the Buddha. Kaliyan, having heard of this statue and being in desperate need of money to build the enclosure wall at Srirangam, decided to rob this golden Buddha. I can almost hear what you say, “But of course,” here’s the man who sees the lord everywhere and who has been bid by his lovely consort Kumudavalli, to tend to the work of the Lord. Riding his white steed Aadalmaa, the warrior poet set off to Nagapattinam and stole the Buddha in the middle of the night. While en route to Srirangam, it was here at Tirukkannangudi that he buried the Buddha for safe-keeping. This bold strike seems to have been a terrible blow to the growth of Buddhism in the region. A small hamlet, the temple and its environs are markedly distinct in one key aspect from the others in the region that we have visited till now. It is barren – even in the pitch dark of the twilight we can see the barren lands, the absence of water bodies that seemed to pop into view around every corner till now and the presence of just thorny bushes and brambles. It is said to be because of the curse of Kaliyan. when he was refused hospitality and place for the safe-keeping of the Buddha statue; the Azhvar in anger is said to have cursed the place to remain barren till eternity, so generations of visitors know the people’s apathy to Vaishnavism!

But not so the scene that follows. Yet again emerald green fields beckon, and delightful rivulets and ponds adorn the sides of the road as we finally depart Kumbakonam to our final destination. Tiruvali lies a little way off the national highways between Kumbakonam and Sirgazhi. Every petty shop along the highway worth its two cents knows Mangaimadam and Azhvar’s birthplace.

Mangaimadam is where the poet married the damsel he loved, the beautiful Kumudavalli to whom the religion owes the making of its versatile Azhvar. Now there is a dirty mud road bustling with bus stops and stores selling everyday things as wares. Right behind that is where he bit the toe of a newly-wed groom, the Lord himself in disguise. The tribal chieftain by now was a waylaying robber, who burgled his way through the feeding of the 1000 Vaishnavites a day, undertaking repair works at temples, all in an effort to woo his Kumudavalli. Having heard of a party of newly-weds, he robbed the group relieving them of all their riches. One imagines the Azhvar’s thought process:

“And what was that? A shiny toe ring that hadn’t been removed from the groom. That could certainly fetch enough to feed a few thousands more. And why isn’t anyone in my thieving gang able to remove that? Here, let me try, shouldn’t let these nincompoops in charge of anything. Phew! That’s tight. Well, maybe not so tight with my teeth now, that will wipe the silly smirk of the groom’s face. He does looks extremely attractive though and vaguely familiar, like I have seen him somewhere, no, everyday. That is strange, he doesn’t wince when I bite and tug at the ring. Now I have a better grip, there, pull, pull. Wait, that’s not metal at all, it’s his toe, but it isn’t like anything I have tasted before, it’s honey, no, it’s the very nectar of the devas. Oh, heavens! Now I know where I have seen him, why I think I have seen him everyday. When I close my eyes now, it is him I see in me, and it is him I see outside me, he is the sky, he is this blinding light that pervades all this space, all these people, he is all of them, he is me, he is everything.”

Wasn’t that the moment that defined the personality, the very being of the Tirumangaimannan from then on?

The very song of the decade dedicated to Tiruvali temple lord is particularly poignant here. Azhvar sings,

I dropped at your feet upon which you penetrated my heart

following your entry I prostrate, my

sweet muse

oh! lofty one, my cherished life

Just past the place following yet another green spread, the ubiquitous water body is a tiny temple, a dot on the landscape which is pointed out as the birthplace of the Azhvar. We drive past that, only to reach a better place.

We almost jump out of the running vehicle, hurrying to get past the temple doors, which close at nooneveryday. The words of another Azhvar come to mind here. Periyazhvar – the father of Andaal, the renowned female Azhvar who married her divine lover, the Lord – sings of the jubilation in Gokul at the birth of Lord Krishna. He says, that the inhabitants in their madness and excessive joy, ran and jumped so their feet hit their posteriors! That is how we must have appeared to the onlookers at the main street that ends at the temple at Tiruvali. It is a calm street with a neat , broad mud track. The houses on either sides are straight from the pages of Malgudi days. Low, long houses with terracotta tiled roofs, broad thinnais in the front porch with slender, ancient, wooden columns and no people outside. It is deserted. Everyone excepting us mad city folks have of course retired to their noon siesta after a heavy meal. We rush, the temple door is open, but no. the priest says, the sanctum sanctorum doors are locked, and we have to return at 4pm.

We have waited an entire week – no, an entire lifetime, some of us confess – so what is a few more hours to us? After a meal at a kind soul’s home, we stretch our limbs and settle to hear folk songs on the bard of the hamlet. Tirumangaiazhvar is the folk hero in these parts.

The folk song here recounts more tales of mischief. The lines talk of the time when the bard employed a few masons and carpenters for the Srirangam enclosure wall work. Once the work is completed, the workers want payment. And what does Kaliyan do? He pushes them into the Kaveri river, saying they will attain the abode of the Lord, Vaikuntam, for their service to him! And legend has it that they did indeed!

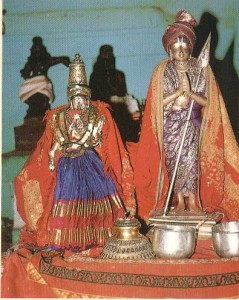

It is 4pm. Our wait is over the journey has come to its finial. Atop steep steps that lead to the sanctum sanctorum, there, standing with his very beautiful, big-eyed Kumudavalli, is the poet we have longed to see. His matted locks, coiled atop his elegant head, include a turban as the Margazhi festival is still on. There is the slightest of bend in his posture near his hip that make his posture more graceful and yet more manly. The broad shoulders tell the tale of countless battles. His handsome features arrest our eyes. We are unable to turn around to view the Lord. The spear gifted him by Tirugynanasambandar, the Saivite Nayanmaar, rests on his broad chest as would a drop of water on a lotus leaf, yet it is his hands that are joined in loving supplication and the ever gentle bend of his head in a bow of subjugation that make him our Azhvar.

A protagonist who evolves from a mere mortal to a stellar proponent of ideals, is more appealing than one who is born righteous. The former gives moral strength to the reader. The reader identifies with his slips and falls and applauds with enthusiasm when all is well. Azhvar taught people that committing mistakes is human but to acknowledge them and conquer them to step higher is the lofty purpose of the soul.Through his songs, we have followed the saint through his downfalls, his mortal love and we have watched him morph into the champion of social equaliser – love for the lord. We have cried, laughed and played coy with him through his songs. We have relished the lord through his eyes, we have fallen in love and thrilled at His every curve and decadent feature. Having held the Azhvar’s hands thus far, we have been led through the greatest heights of love. It is now time to prostrate before his majestic allure and take leave. We leave carrying his words and his valiant love.

Hail Azhvar!

Preeti Madhusudhan is a freelance architect/ interior designer living in Sydney with her husband and eight-year-old son. She is passionate about books and is an ardent admirer of P.G.Wodehouse. She inherited her love for books and storytelling from her father, a Tamil writer. Preeti is trying to publish her maiden novella in English.

Pic from http://thoughtsonsanathanadharma.blogspot.in/2013/01/thirupavai-pasuram-15.html

a different kind of travelogue indeed. one never tires of travelling in the Kumbakonam belt of Tamilnadu, south India. it is all green, despite low rainfall, almost dry Cauvery river and general apathy of all concerned to keep it in its glory. probably Kaliyan’s Tamil poetry keeps the area still good.