by Anupama Krishnakumar

Anna has been keenly studying the photograph in her hand for about fifteen minutes now. She is surprised at how new it looks inspite of the fifty years that has lapsed between the time it was clicked and now. The photograph had been a chance discovery. It had fallen, quite cinematically, from between the pages of one of the books that Anna inherited from her bookworm mother upon her death.

The books, about five hundred in number, have remained her biggest dilemma in a long time. At fifty five, she had been bogged down by bigger problems in life but she somehow finds this alternating between choosing to keep the books and donating them to a library or discarding them, terribly unsettling. On the one hand she thinks it would be unfair on her part to give away the books on whose every single page lay invisibly, the impressions of her dear mother’s touch. On the other, she often mulls sadly over the futility of holding on to things in the name of memories.

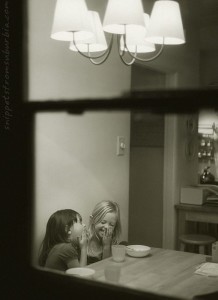

In that moment pregnant with the indecisiveness that periodically haunts her, Anna flips the photograph over and finds her mother’s neat handwriting in green ink. “A moment of childish happiness: Anna and Betty sharing a warm joke. Giggling girls indeed. Dated 20th June 1975”. Betty. Betty, Anna thinks again, as she peers into the face of the little girl beside her own little self. Betty, her first best friend, is all but a vague memory now. Like all things that flow, Betty had moved away too from England to the U.S., and Anna remembers this because the memories of her older years have no trace of Betty. Whatever she can recall of Betty is what her mother had told her as she grew up. You know you and Betty poured an entire bucket of water over poor Rosso, your little brown teddy bear, Anna’s mother told her once, laughing a little. And she told her many more such tales of mischief with her little friend, events that Anna had no memory of.

Anna smiles a little when she thinks of how her mother would scribble little memory notes behind all photographs, in an effort to preserve moments timelessly. After all, photographs were such a rarity back then, unlike now when every damn event, however insignificant, finds a place in a mobile phone’s camera roll – something that Anna finds clearly annoying.

There are many thoughts criss-crossing each other in Anna’s mind. Her forehead creases in interesting patterns reflecting her thought process, following sincerely and meticulously the various emotions raging in her head: Curiosity, Longing, Regret, Realisation. She tries hard to recall what she and her dear friend were laughing about. She wishes deeply that her writer-mother had added a few lines about what the two little girls were talking about. Despite the restlessness that seizes her heart as she tries to demystify a conversation from fifty years back she has no clue about, she can’t help but admire her mother’s artistic eye. The way she has composed the shot, Anna thinks, is so beautiful. She imagines that her mother perhaps decided to not be an intruder and disturb the moment of childish innocence and union but capture its uniqueness, timeliness and essence by staying the non-invasive outsider.

It’s hard for Anna to think of herself as a child that she even wonders if she could have ever been one. Life, with its whole bundle of experiences and challenges, Anna thinks, leads to one feeling like a solid, inert mass of flesh, and wondering helplessly what it would have been like to be a little human being throbbing with life and freshness. She suddenly feels like letting out a huge wail as she yearns to be a child and go back to living life all over again. She would then undo so many, so many things! But wail she doesn’t, for her age forcibly clamps down on her, a reminder to maintain her decorum, and therefore, she weeps, quietly.

Where would be Betty be now, Anna wonders next. What would she be doing this very moment? Would she remember Anna, her first childhood friend? What would life have given Betty in all these intervening years? Would she have lived through a similar set of experiences like Anna had? High school, college, love, marriage, kids, career, divorce in that twisted hell of a thing called life. Would she too have peaked with confidence and fallen to the lowest levels of self-esteem at various times? Would she too have longed for that soul mate of a friend during times of distress? Would she be like those self-confident women who put themselves above everything and everyone else? Or would she have turned out to be a woman who was trampled by the reckless forces of patriarchy? And then Anna wonders how Betty would look now. All grey-haired and wrinkled, ageing gracefully? Or would she be a picture of someone worn down by the brutality of existence? And lastly, with a tinge of fear and anxiety, Anna asks herself the worst question: Would Betty be alive at all?

As Anna, with a head full of thoughts, draws a deep breath and looks back at the picture, a short and round woman turns restlessly about in her petite bed in another part of the world. In her dreams, she sees a woman in a black dress holding a photograph in which there are two little girls giggling. Betty sees herself and the other girl, and in her sleep, her lips part to utter a name. Anna. Anna, she says again, now with her eyes slightly open. A smile punctuates that utterance and Betty falls asleep again. Elsewhere, Anna puts the picture back into its place between the pages again and postpones the decision over her mother’s books to another day. That, she thinks, can wait. For some more time.