by Suresh Subrahmanyan

Guilt for being rich, and guilt thinking that perhaps love and peace isn’t enough and you have to go and get shot or something − John Lennon

How eerily and tragically prophetic were those words of the slain Beatle, John Lennon. ‘Guilty conscience pricks the mind’ was one of our oft-repeated aphorisms in boarding school whenever one of the boys protested his innocence excessively over a hockey stick or cricket bat mysteriously gone missing from the dormitory. This was usually chanted by several boys in choral unison in a mockingly musical tone, embarrassing the accused no end. That was one of the first lessons we learnt. Never volunteer your ‘not guilty’ plea vehemently when the jury is still out deliberating. And for God’s sake, do not blush. You might as well say, ‘Sir, I did it’ and face six of the best. Puts me in mind of Queen Gertrude’s words in Hamlet – ‘The lady doth protest too much, methinks.’

The concept of guilt, therefore, was inculcated in us at a very early age. We could lie through our teeth at will only to escape punishment. In a worst case scenario, we would simply point our accusing finger at some other poor sod. ‘Warden Sir, Shankar did it. I saw him with my own eyes. God promise.’ We had no problem invoking the Almighty into the proceedings if that was the last resort left to us. After all we were taught that God will forgive anything if you admitted your wrongdoing. That unalterable belief cut across all faiths. We did resort to such cold comfort when we went to bed nightly, praying tearfully and guiltily into our pillows. Felt a bit sorry though for poor Shankar next morning, but the sick feeling of guilt in the pit of our stomachs soon passed. Telling on someone was colloquially referred to as sneaking in school-speak, and if there was anything worse than sneaking in school, it was sneaking on someone falsely, more so when you yourself were the guilty party! An unforgivable sin.

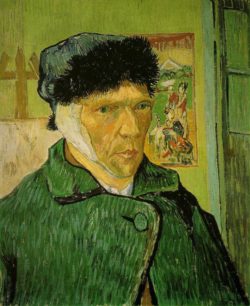

Once so branded, you lived with that unfortunate appellation for the rest of your school life – SNEAK. And your guilty conscience never stopped pricking you, particularly when you had to look at yourself shamefacedly in the mirror daily. Shades of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, in which the oil portrait of the protagonist decays in direct proportion to the egregious and wanton excesses committed by the hero, while the latter remains young, handsome and vigorous. Read the book for the disturbing and brilliant denouement. As one grew to man’s estate, so to speak, and began to realise the folly of one’s youthful days, one wished to turn the clock back, and do things differently, retrospectively. It’s all part of the growing up process. I am reminded of what the Canadian singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell said in one of her beautiful songs. But when I became a woman / I put away childish things / And began to see through a glass darkly. In a nutshell, Joni.

It is one thing to reflect on one’s childhood peccadilloes and be rueful about them, but then you are able to tell yourself that we did all kinds of stupid things when we were young and weren’t mature enough to know better. My own sense is that there are too many of us around who do not learn salutary lessons even after we are well into adulthood. Perhaps our sensibilities harden as we grow old, like our arteries, and we start becoming more subtle, sly and selective in determining right from wrong. We observe this trait in many of our politicians. For this discussion, I exclude hardened criminals, those who steal, rob, rape, pillage, murder, frequently go to jail – and think nothing of it. Sadly, some of our politicians do fit that description. I also exclude the more sophisticated brand of criminals who run corporations, rob shareholders and the common citizen and scoot to foreign lands when things get rough at home. This type of criminal couldn’t possibly spell the word guilt, leave alone feel it.

Another line of speculation can be in the realm of everyday situations where normal people like you and me (I trust we are normal), don’t quite measure up, in our own eyes, for having done or not done something that we ought or ought not to have done. ‘The worst guilt is to accept an unearned guilt,’ said Ayn Rand, and the iconoclastic author of Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged makes a telling point. Many of us who are blessed (or cursed) with a hypersensitive disposition, tend to keep looking for faults in ourselves, and everywhere we turn, we see demons where none exists. ‘Why did he not wish me good morning? Was it because I made that poor joke about his mild stammer? That was in poor taste.’ And then you go and apologise profusely to this real or imagined victim, who proceeds to sit on his high horse, playing the burning martyr to the hilt and piling greater misery on you. I’ve seen that happen to people who tend to cogitate excessively over some harmless, risible remark and worry themselves sick over a non-existent faux pas. A thoroughly wasted and sapping exercise.

Forget about accepting guilt where there is no provocation to do so, the more difficult task is to embrace guilt when you have actually committed a crime, and a heinous one at that. Anyone who has read Fyodor Dostoevsky’s magnum opus, Crime and Punishment, will readily identify with the complex workings of the mind of a man who has accomplished the extraordinary ‘feat’ of murdering two women, back to back as it were, and then goes through the agonizing mental contortion of justifying the crime to himself, and the long and winding process of submitting to the long arm of the law. The great, though highly conflicted, Russian author was not necessarily dealing with just pure guilt on the part of the protagonist, but guilt combined with an unshakeable conviction that his crime was fully justified in his eyes. Psychologically speaking, this is an impossible situation to deal with where the criminal’s mental state veers from one extreme of self-justification and self-righteousness to the other extreme of martyrdom and its dubious self-flagellating rewards. However, his guilt-ridden idée fixe overwhelms him to the point of mental illness. Despite its title, the novel does not so much deal with the crime and its formal punishment as the protagonist’s own demons with his existential inner conflicts. The book demonstrates that his punishment results more from his conscience than from the law. In modern times clinical depression can give rise to the mind yo-yoing wildly even without the patient being guilty of any wrongdoing.

No discussion on any human condition can be complete without delving into the works of Shakespeare. On the subject of guilt alone, we are spoilt for choice. However, I have settled on Macbeth to conclude this essay. Macbeth and Lady Macbeth are tormented by feelings of guilt and remorse throughout the play. The ghost of Banquo is seen as the embodiment of Macbeth’s guilt, shared by Lady Macbeth as they see themselves guilty of the murders of Duncan, Banquo and Lady Macduff. Perhaps the two best-known scenes from Macbeth are based on a sense of dread or guilt that the central characters encounter.

First is the famous soliloquy from Macbeth, where he hallucinates on a bloody dagger, one of many supernatural portents before and after he murders King Duncan. Macbeth is so consumed by guilt that he’s not even sure what’s real. Is this a dagger which I see before me / The handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee. Only to be matched by Lady Macbeth’s own torment, washing away imagined blood, symbolising her guilt. Out, damned spot! Out, I say! / One, two. Why, then, ’tis time to do ’t. Hell is murky!…….. Here’s the smell of blood still; all the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand. This is the beginning of the descent into madness that ultimately leads Lady Macbeth to take her own life, as she cannot recover from her feelings of guilt.

It is easy to conclude that guilt is counterproductive, but who amongst us has not felt its corrosive pangs? So long as we do not take another’s life, we can hold it in check, and learn from its deleterious effects. However, if we are to go with Dostoevsky, even murder is fair game. The end justifies the means.