by Kousalya Sarangarajan

Sitting in a window seat in the Rameshwaram express – which I had to fight for with all my might with my brother – I gazed at the sea of green, studded with creatively-put-up scarecrows. I saw the train taking a curve, hugging the landscape; I stuck my head to the window as much as possible, craning my neck to see when the back of the train would disappear as it finished rounding the curve. Having seen the end of it, I turned around to look at the sulking face of my brother. “What’s the matter Kumara?” I asked. “I hate going to paati’s house. Maama will ask me to clean the buffaloes there!” I gave him a knowing smile and turned back to the sights that bewitched me. My heart sang with happiness at the prospect of cleaning the buffaloes. Kumar did not know this, but maama had let me in on a secret last summer. That summer, maama had promised me that I would be given the responsibility of bathing Maheshwari, the buffalo, this year. He told me that if I scrubbed Maheshwari with a softened coconut fibre, she would become a milky-white cow! He also told me I could claim the cow-buffalo mine. He added that he found that I had an exceptional hand at cleaning things and that he was letting only me in on the secret of converting a buffalo into a cow. My heart swelled with pride. I was singled out from among a group of five cousins, all older to me. My uncle did not find anyone fit enough to convert a buffalo into a cow. I was chosen because I was special. I was ecstatic.

My vacation goal was set. Maheshwari was going to undergo a change and when she would gaze at her reflection in the village pond, Maheshwari would be so grateful to me. She would not kick me when I tried to milk her and she would forever be mine!

Maama came to pick us up from the station. We all crammed into the bullock cart smelling of hay and happiness. Radhika, Kumar and I sat facing the road, our legs dangling over the edge of the cart, holding on to the kondi, a single bar of iron that served as a gate to prevent the inmates from falling off the cart. Reaching Swamimalai took considerable time. At the end of a long journey, the bullock cart stopped outside the familiar house, and the familiar scene of paati and thatha seated on the huge thinnai with beaming smiles on their faces announced the start of yet another lovely summer.

Every morning, when the birds chirped away, I would wake up with a thrill. The thought that Maheshwari would get whiter that day was enough to drive away any vestiges of sleep from my body. Paati would offer a large tumbler of hot creamy milk that smelled faintly of her kitchen, we would finish our morning chores and wait for maama to accompany us to the cowshed. All of us had to help maama at the cowshed in the morning before we were allowed to play on the dusty streets or the tamarind groves at the backyard. We were never allowed to work there without maama around. I hated the way he used to troop about as if he owned the place and the inmates. The other cousins used to make faces at the prospect of going to the cowshed. They only worked when they thought maama was noticing them. There was no sincerity in their work. They only had to clean the cows, not the buffaloes. As if that was a difficult job!

Mama cleaned the bull Hari. My cousin Shruthi had to make the prasadam for the cows and buffaloes, laddoos of wheat and jaggery. I had the most difficult job of converting a buffalo into a cow, but I never complained. I guessed why maama did not tell them the secret of making a cow out of a buffalo. Only I knew that diligent scrubbing and words of love and encouragement to the buffalo would help it transform! I wished with all my heart for my cousins and my brothers to behave well so that they too would also get that golden opportunity. Maama had three cows, Lakshmi, Rukmini and Radha. He told me in hushed whispers they were all buffaloes when he was born. His mother, my paati, had entrusted him with them when he was 10 and he was able to scrub and wash them so well that they became cows by the time he was 11. He regaled me with tales of how he used to have a set pattern of cleaning the buffaloes, then helping his father clean the shed, offering them the prasadam, some hay and water, before squatting down to milk them. I knew he was not exaggerating. The cows and buffaloes in the shed loved him.

Day after day, I would clean Maheshwari and go and whisper to maama, asking him to come and inspect her and give me a certificate of “good job”. With this routine going on, the summer of 1977 came to an end. On the last day, maama took us all for a last bath at the pump set in the fields, where we splashed about like fish in the water. He then took us to a special place in the field where he would have his afternoon meal with other farmers. A swing from the branches of the old arasa maram moved in the breeze, and we took turns on it while waiting for the other farmers to join us. After finishing a tasty meal put together by paati, maama gave away prizes to all of us in front of the other farmers. Kumar, Saravanan and Satish were gifted whistles made of leaves from the arasa maram and coloured marbles. Radhika and I got a pair of blue ribbons and he proudly announced to all that Maheshwari had become fairer under my expert care. My cousins sniggered, my brother laughed. There was no end to jealousy in this world, my wise heart told me. The farmers exchanged looks and clapped enthusiastically. I stood up and said, “Thank you maama! I want to follow in your footsteps,” and gave him a special wink, and he winked back acknowledging our precious little secret.

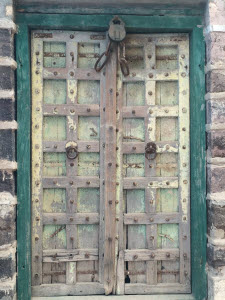

Picture from https://www.flickr.com/photos/nitinbwrd7678/

Narrated beautifully . Able to visualise the rustic nature and naivety of the little girl.

Super Kousi. Very Nice

Regards

Anand

Loved it kousi. The innocence of childhood, small cute things in village life is depicted very beautifully. Keep going..